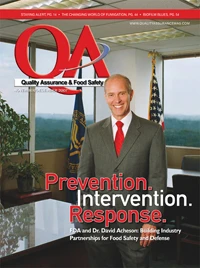

It is a study of contrasts, symbolic of the agency itself.

I had come to the U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA) building in Rockville, Md., just outside Washington, to meet with Dr. David Acheson, newly appointed assistant commissioner for food protection, and discuss his position, his plans and goals and the general direction of the agency itself.

As has occurred in facilities across the U.S. since Sept. 11 — airports, government buildings, schools and processing plants alike — FDA has increased its building security, limiting access and conducting preventive measures. In this case, extensive measures require a full ID check and employee escort; the visitor — and employee — must then also pass through metal detectors, an X-ray scan of all possessions and, even once inside, an escort/visitor badge comparison and verification. All of this is overseen by stern security guards, ready to intervene at any hint of noncompliance. Though understandable in today’s world, the measures served to reinforce the general preconceived notion of governmental regulatory stringency and bureaucracy.

Yet once I was finally granted access, once I was face-to-face with the real FDA — that is, its people — the rigidity fell away; the response held the accommodating, collaborative air of a partnership.

Prevention. Intervention. Response. The three principles, so evident in the physical structure of FDA, have been identified as the basis of the agency’s food safety strategy to better protect the American public and U.S. economy from food safety and defense threats.

It is a strategy, however, in which industry must also be vested, explained Acheson. “What I want the industry to know is that I regard it as a partnership,” he said. “I would not like industry to see our approach here as a heavy-handed regulator. I would like them to see this as more of a two-way discussion.”

Acheson took on the newly created position of assistant commissioner for food protection in May. As assigned by Commissioner of Food and Drugs Dr. Andrew von Eschenbach, a key task of the position is the development of a strategic, trans-agency approach to all food safety and food defense issues. “Hence, its title: ‘Food Protection,’ which encompasses both,” Acheson said.

“The commissioner recognized the need to coordinate all agencies under one leadership, and he created this position to do that,” Acheson said. “A lot of things had happened and the systems hadn’t necessarily kept up.” To rectify this, Acheson has been charged with development of a plan focused on what needs to be done now and into the future.

As Acheson explained in an earlier FDA/USDA media teleconference, the goal of his position “is to develop a strategic way of thinking, moving to the future, acknowledging that there’s been change in recent years with regard to food safety and food defense on both a domestic and the import front and develop a strategic vision to tackle that” — i.e., prevention. The second and third components of the position focus on crisis management — coordinating situations of significant health hazards related to food and feed that cross multiple sectors of the agency, i.e., intervention and response.

PREVENTION. According to Acheson’s September statement before a Congressional subcommittee on food safety: Prevention is the cornerstone of an effective, proactive food defense and food safety strategy. The implementation of preventive control measures by industry is essential to prevent intentional or unintentional contamination of the food supply. In the prevention arm of FDA’s strategy, the agency will develop scientific and analytical tools to better identify and understand risks and the effectiveness of control measures used to protect the food supply.

The focus on prevention actually is a shift for FDA, and is critical to food safety and defense strategies, Acheson said. “We had evolved to being somewhat reactive. It is good that we are reactive, that we can react, but the three components really begin with prevention.”

Prevention also is the area in which the industry can have the greatest impact, he added. “We say that industry has a responsibility to produce a safe product. I believe that there’s no question about that.” In addition, though, Acheson said, “They are the ones who are in the best position to put preventive controls in place.”

A RISK-BASED APPROACH. To do so, however, industry has to know how to implement preventive controls and understand where the risks lie, incorporating a science-based approach. And, in fact, the industry has such an approach in place now — HACCP. “I’m not saying that we need to apply HACCP across the board, but the HACCP concept, which is really a risk-based way of thinking, is something that I think industry — whether they recognize it or not — largely do,” Acheson said. Some plants have formal HACCP implementations and requirements, but many simply apply HACCP concepts because they make sense.

Additionally, HACCP concepts can apply just as well to food defense as they do to food safety. “It’s very similar,” Acheson said. “It’s all about risk. It’s about looking at your system and asking yourself, ‘Where is it vulnerable to deliberate attack?’” Although this requires a different mindset, he said, “as we put preventive controls in place, we need to be thinking about unintentional contamination.” For example, knowing that an open conveyor belt can create a food safety hazard of contaminants falling into a product, the plant should also see the food defense vulnerability of intentional contamination at the same open point. When determining food safety solutions such as covering the line or eliminating drip potential above it, food defense solutions such as limited access also should be considered.

Acheson acknowledged that some plants feel that food safety and food defense initiatives should be completely separate because of the differences in intentional and unintentional contamination, but he does not see this as the best use of resources. He said FDA is seeking to merge safety and defense, with enforcement and response — particularly at the state and local levels — remaining with the same person.

POSING THE QUESTIONS. “What I see (FDA’s) role as is working with the industry members to help them understand where preventive controls might work,” Acheson said, posing the questions and establishing a scientific basis for the answers. Taking the 2006 spinach E. coli outbreak as an example, the question is: How exactly did the spinach get contaminated? Even knowing that E. coli can exist in the soil, water and cattle — how did it get to the spinach field? Then from these answers, asking: What are the optimal preventive controls by which the industry could minimize the likelihood of contamination? If we know the E. coli originated in cattle, how much distance should be maintained between cattle and growing fields — five feet? Five miles? Across the state? “What is the science behind that?” he asked.

“You have to develop all the preventive controls based on science. But,” Acheson emphasized, “you have to make sure you’re not paralyzed in the absence of science.” While there may be times when one would wish to have more data before proceeding with a plan, you can’t always wait until all the t’s are crossed and i’s are dotted to take any steps, he explained.

FDA itself is not a research agency, he added, but it can help drive the questions and ensure that the research agencies and academia are aware of the questions so they can target their research in a relevant manner. And, he added, “we can make sure that when that research is done, we communicate it to the industry.”

INTERVENTION. The second step in FDA’s food safety and defense strategy is that of intervention. As described in Acheson’s September statement: Risk-based intervention supplements the prevention arm of FDA’s strategy. Intervention includes monitoring the success of, and identifying weaknesses in, preventive measures. Intervention augments prevention through inspection and sampling techniques that use modern detection technology. Intervention relies on information technology systems to improve FDA’s ability to target and conduct inspection and surveillance, perform laboratory analysis and achieve reliable 24/7 operations.

During the last few years, both FDA and USDA have transitioned toward risk-based inspections which, as the wording indicates, focus on areas of greatest risk, determined by factors such as product, history, source and science. While the strategy does help the agencies improve resource allocation in a time of reduced funding, it also is simply a logical approach.

This strategy is particularly applicable when focusing on the global food chain. “Unless the agency had a staff of hundreds of thousands, there’s no way we could inspect everything,” Acheson said. “We never will — and personally, I don’t think we ever should. There is not a cost benefit to the American consumer to do that.”

RISK-TARGETED INSPECTIONS. Rather, Acheson said, the goal is to target inspections to those products with the greatest potential risk. “You need data to determine that; and that data, very importantly, is dependent on what’s going on in foreign manufacturing facilities.”

One of the issues, he said, with inspecting goods at the point of entry into the U.S. is that this approach is just “a snapshot in the lifecycle of the product.” That is, the inspection is a single-point depiction of the product’s supply chain, with the inspector rarely having the necessary insights or data to tell him if a shipment should be inspected.

“How much better would it be if that inspector was armed with information pertaining to the manufacturer in country X?” Acheson asked. Does the country have a questionable water supply? Do they use preventive control programs? “We don’t really know what is going on as much as we’d like in the foreign manufacturing facilities,” he said.

IMPORTED GOODS. The China situation is a good example of the “snapshot” issue. While recent recalls have helped focus high-level decision makers on the fact that “imported food needs a little work,” Acheson said, it’s also somewhat misdirected global attention. “Consumers have got it into their heads that it’s all about ‘Made in China’ and if we shut the borders to China, all the problems will be solved. That is so not true.

“We’re seeing more problems with China partly because of the volume,” he said. China is growing at a tremendous rate and exporting vast quantities of products; the sheer numbers lend themselves to increased issues. Strategies must be applied across the board, not just to certain countries. “We import food from about 230 countries and regions into the U.S. We’ve had problems with multiple other countries.”

FOOD DEFENSE APPLICATIONS. Such risk-based intervention applies as well to food defense as to food safety. While the industry is aware of the potential for intentional contamination, many still hold the ‘it-won’t-happen-here’ mentality. “It hasn’t happened, but it could,” Acheson said. “And if it did, it would be devastating psychologically, economically and potentially public health-wise as well.

“What we can’t do is build independent food safety and food defense systems,” he added. “We have to integrate them. That’s where my title — food protection — comes from.”

With improved intervention technologies, FDA could “push that border out so we have much better insights as to what’s going on with that foreign manufacturer.”

And that leads back to industry partnerships. “The domestic industry has huge insights to what is going on overseas,” he said. FDA needs to build industry confidence and interaction, and work with the foreign governments themselves. In this way, Acheson said, the agency will be able to prioritize inspections based on risk and, ultimately, provide the U.S. industry with incoming goods that are deemed to have less risk.

RESPONSE. While FDA is working to shift its — and industry’s — primary focus from reaction to prevention, it also is working to improve reaction, focusing on trans-agency coordination, strategies and, again, increased science, to reduce response time, increase communication and limit the economic impact.

As defined in Acheson’s statement, the response arm of FDA strategy reduces the time between detecting and containing foodborne illness. FDA’s recent experience with spinach and leafy greens, melamine, peanut butter and other contaminated products demonstrates the need for more effective response strategies. FDA must respond faster, communicate more effectively to consumers and FDA food safety partners, and limit economic hardship to the affected industries. FDA also must further integrate response systems with state, local, federal and international agencies.

The goal, Acheson said is to build the strategies — prevention, intervention and response — off industry best practices. “It’s not to reinvent the wheel. A lot of folks out there have done a lot of thinking about how to prevent contamination and what to do about it.” Compiling practices from various companies, gaining knowledge from subject-matter experts, incorporating science-based research and results all are critical to improving the food safety and defense structure of the U.S. Acheson’s goal is the coordination of this improvement.

INDUSTRY PARTNERSHIP. “It has to be a partnership,” Acheson emphasized. “I do not believe FDA has all the answers. We need to work with industry jointly to do that,” he said, explaining, “Our mission is to protect public health. The industry’s mission is to not make people sick … to do everything in their power to prevent that in the context of the business decision.

“At the end of the day, the responsibility — from the consumer’s perspective — of preventing people from getting sick is often put at our door,” he said. “But as I see it, it’s largely industry’s responsibility. Our job is to make sure that they do that and make sure they do it right.”

I entered the FDA building seeing the steel and stringency of its security as fairly indicative of the agency itself. But in the two hours during which I visited with Dr. Acheson and interacted with FDA people, my preconceptions were gradually unraveled then reaffixed into an understanding of the necessary contrasts of this federal food-protection organization. While today’s world can sometimes, unfortunately, demand heavy-handed regulation, the people behind those regulations, the people responsible for carrying them out for the protection of public health, are … people. Gracious, accommodating, genial — yet possessing a profound commitment to working with the industry to develop the prevention, intervention and response needed for the attainment of global and domestic food safety and defense.

It is a contrast necessitated by the world in which we live — a contrast that looks to bode well for the industry’s future.

The author is Staff Editor of QA magazine.

Food Safety and Security Summit

With its theme of Everyday Heroes, it seems a logical choice for the 2008 Food Safety and Security Summit to include Dr. David Acheson, FDA’s assistant commissioner of food protection, as a keynote speaker.

One of Acheson’s primary goals in his recently attained position is the melding of partnerships between government, academia and industry to focus on improving and increasing both the safety and security of the U.S. food supply.

Similarly, the summit’s theme — “Food safety is no accident.... Ensuring the safety and security of our food supply chain takes everyday heroes” — reflects a partnership that flows throughout the food supply chain, involving every person at every level.

“From farm to fork, everyone in the supply chain is considered a hero,” said Scott Wolters, director of tradeshows and conferences for BNP Media, which owns and operates the event. “All the way through, there are all these people who have something to do with food products or food. They are everyday heroes because they do such a great job of ensuring the safety of the food chain.

“In today’s world, there is such an awareness of food safety and food quality,” Wolters said. “Food safety is not just an industry-related topic anymore; it’s an overall, over-reaching consumer and industry business that requires everyone to pay attention to what they are doing.”

And it is just these requirements that the summit addresses. Sponsored in part by QA magazine, the summit focuses on practical application of food safety and food security practices and includes two and a half days of educational seminars, workshops, social and networking events, and an industry-vendor exhibit hall. Entering its 10th year, the summit will be held March 17-19 at the Washington (D.C.) Convention Center.

In addition to Acheson, the event will feature two other keynote speakers: Rick Frazier, senior vice president of technical stewardship for the Coca-Cola Company, and Richard Rivera, chairman of the board of the National Restaurant Association.

New at the summit for 2008 will be an educational poster area for display of academic research, a new product showcase venue on the show floor, and an expansion of the show-floor vendor track theater where exhibitors can stage educational presentations on their areas of expertise.

More information on the summit and registration forms are available online at www.foodsafetysummit.com or by calling 847/405-4030.

Making an Impact on Health: from Patients to Test Tubes to National Policy

Dr. David Acheson began his career as a practicing physician, spending a decade in that field. He transitioned to university research in microbiological pathogenesis, working with E. coli at the time it was first described. Then, as his role in the public health aspects of food safety grew, he joined the government, serving both USDA and FDA in roles of increasing leadership.

In May, Acheson’s extensive background and expertise led to his being named to FDA’s new position of assistant commissioner for food protection.

He is tasked with providing advice and counsel to the agency’s commissioner on strategic and substantive food safety and food defense matters; working with FDA product centers, as well as the Office of Regulatory Affairs to coordinate FDA’s food safety and defense assignments and commitments; and serving as the commissioner’s direct liaison to the Department of Health and Human Services, of which FDA is a part, and to other departments and agencies on food safety and food defense related inter-agency initiatives.

ACROSS THE POND. Acheson graduated from the University of London’s Westminster Medical School in 1980, and completed his medical training in the United Kingdom, specializing in infectious diseases. When granted a fellowship at New England Medical Center and Tufts University in Boston, Acheson became the principal investigator on a number of studies of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli.

Since then, he’s built an extensive pedigree in protecting public health: a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, London, and of the Infectious Disease Society of America; an editorial board member of the journal Infection and Immunity and special editor on food safety for the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases; a member of the National Advisory Committee for Microbiological Criteria for Foods since 1998; and service on World Health Organization working groups as well as National Institutes of Health advisory committees.

By the early 2000s, Acheson had become an internationally known expert on E. coli and foodborne disease, with a specialty in public health and the molecular pathogenesis of foodborne microbes.

EXPANDING HIS IMPACT. After a decade as a practicing physician, Acheson said, “I gave up interacting with patients and started interacting with test tubes.” His studies focused on the fundamental questions: If you eat a contaminated piece of food with E. coli O157:H7 on it and end up in the hospital, what exactly was it that that food did to you to cause the illness? From this, he explained, you then figure out how to treat it and how to prevent it.

When Acheson began his studies of E. coli, many physicians weren’t even aware of its existence, he said. “I was very much in the right place at the right time, working on a bacterium that people had an interest in.”

As his studies and career continued, Acheson said, “I found myself more and more involved in the public health aspects of food safety and spending more time communicating the food safety message to the media and the public.” So when, in 2002, he was asked to take on the role of chief medical officer for the FDA Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), “the time was right,” he said. “It was time for a change.”

“Working at a bench, you have little direct impact on public health,” he said, explaining that lab work is focused on the long-term, but doesn’t have a direct effect on people. So, he decided: “Let’s do something that will have more direct impact.” As a physician he was able to have such impact — one person at a time; with FDA he would be able to affect national policy. “You can have a major impact on public health,” he said.

A RISING STAR. Acheson’s impact continues to increase, as he took on the additional responsibility of CFSAN Director of the Food Safety and Security Staff in 2004. In this role, Acheson was more directly involved in the operational aspects of foodborne disease illnesses, consolidating areas of the center for efficiency and growing his group from 15 to 100 people to focus on understanding and responding to risks in the food supply.

Through this process, Acheson said, he saw a number of FDA systems that were not working well and needed to be “fixed.” When he was offered his current position in food protection, he saw it as an opportunity to take a more active role in making changes for the benefit of public health.

One of Acheson’s first initiatives in his new position was the roll out of a new Food Protection Plan, made public in November. The plan addresses the changes in food sources, production and consumption and presents a strategy for building upon and improving the protection of the nation’s food supply from both unintentional contamination and deliberate attack.

Acheson Takes the Reins at CFSAN

With the departure of Robert Brackett, Dr. David Acheson was named acting director of the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) Nov. 23.

Acheson came to CFSAN as chief medical officer in 2002, and then became the center’s director of food safety and security staff in 2004. He was named assistant commissioner for food protection earlier this year.

Brackett left FDA at the end of November to take a position as senior vice president and chief science and regulatory affairs officer with the Grocery Manufacturers/Food Products Association (GMA/FPA).

FDA will conduct a nationwide search for a permanent director.

FDA's New Food Protection Plan

Current trends in food production, consumer demographics and consumption, and new and emerging threats have created new challenges for the food industry and, in many cases, served to increase consumers’ susceptibility to foodborne illness.

To focus on such risks across a product’s life cycle and target resources to achieve maximum risk reduction, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) introduced a new Food Protection Plan in early November. FDA is responsible for the safety of approximately 80 percent of the food sold in the U.S.

The plan is intended to incorporate science and modern information technology to identify potential hazards in food safety and food defense and counter them before they can do harm. To address safety and defense in domestic and imported food for people and animals, the plan focuses on three core elements: prevention, intervention and response.

As is explained in the plan, the growing challenges brought about by today’s trends require a new approach to food protection by FDA with an increased emphasis on prevention. “While (FDA’s) level of response needs to be maintained and even enhanced, there is also a need to focus more on building safety into products right from the start to meet the challenges of today,” according to the plan. To do so, this increased attention to prevention requires closer interaction with growers, manufacturers, distributors, retailers, foodservice providers and importers, as well as foreign governments “which have a greater ability to oversee manufacturers within their borders to ensure compliance with safety standards.”

This shift toward prevention is at the core of the plan “and will be evident immediately as the FDA begins an industry-wide effort to focus attention on prevention, from general best practices for all foods to the possibility of additional measures for high-risk foods.”

Following prevention is the strategy of intervention, intended to “verify prevention and intervene when risks are identified.” Taking the form of targeted inspections and testing, successful intervention will verify that preventive controls are working, confirm that resources are being applied to areas of greatest concern, incorporate enhanced risk analysis, and use new detection technology for faster analysis of samples, with a fully integrated food protection system identifying signals that indicate the need for intervention.

Responding rapidly and appropriately will mean that FDA will work with food safety partners to react more quickly “when signals indicated either potential or actual harm to consumers.” In addition, the agency will develop faster, more comprehensive consumer and industry communication strategies.

Included in the 20-plus-page plan are specifics further detailing each of the three core elements, including, for each, itemization of each of the key components, initiatives to strengthen FDA actions, and explanation of why these actions are important and what they will accomplish.

To implement the plan across the food production chain, FDA also notes four principles to be enacted:

- Focus on risks during a product’s life cycle, from production to consumption.

- Target resources to achieve maximum risk reduction.

- Address both unintentional and deliberate contamination.

- Use science and modern technology systems.

In the plan’s conclusion, FDA reiterates its mission to protect and promote public health and its commitment to aggressive pursuit of the plan to keep our nation’s food among the safest in the world. At the same time, however, it also emphasizes the responsibility of industry and the partnership required for protection of the nation’s food supply.

“In the United States, market forces give companies a strong motivation to be vigilant and even innovative in ensuring food safety. The laws of regulation must encourage, not disrupt, these motivations. Rather than taking over responsibility from food companies, FDA wants to protect their flexibility to pursue it vigorously.”

Explore the December 2007 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- FSIS to Host Virtual Public Meetings on Salmonella Framework

- Climate-Smart Soybeans Enter U.S. Market

- Yoran Imaging Introduces Thermal Imaging-Enabled System for Induction Seal Inspection and Analysis

- GDT Highlights Food Safety Solutions for Food Processing and Packaging Facilities

- FSIS Issues Public Health Alert for Ineligible Beef Tallow Products Imported from Mexico

- Wolverine Packing Co. Recalls Ground Beef Products Due to Possible E. Coli Contamination

- McDonald’s USA, Syngenta and Lopez Foods Collaborate to Help Produce Beef More Sustainably

- Divert and PG&E Announce Interconnection in California to Address Wasted Food Crisis