If an industry survey were to take place today, it is estimated that 80 percent of food plants would respond that they have a food defense program in place. This is not surprising when you consider that the topic tends to be covered at almost any industry conference, retail customers are increasingly requiring suppliers to have security programs, and federal guidance has been developed for plant programs.

What is surprising, though, is that while these plants probably do have some elements or components of food defense in place, “less than half have food defense plans,” said Lance Reeve, AIB’s director of food defense. A complete food defense plan is based on a vulnerability assessment, has a printed manual with security measures and policies, documents facility reviews, is reviewed and updated regularly and implements corrective action as needed.

INDUSTRY CHALLENGES. While food defense continues to be a hot topic in the industry, the focus does not always filter completely to the individual plant. Food defense was of great interest for a number of years, but because there have been no high profile incidents in the U.S., and because organizations are experiencing very low levels of sabotage, Reeve said, “it truly has fallen to a lower priority level with most organizations.”

One of the greatest challenges that plants face in food defense, he added, is getting the capital to implement security measures. But as the industry faces increasing pressure to implement defense plans, this will need to be overcome. “You continue to have more retail organizations and manufacturers starting to require food defense as a part of food safety programs,” Reeve said

Edward Mather, deputy director of the National Food Safety and Toxicology Center at Michigan State University, agrees that funding is an issue across the industry, in both education and application of the systems. “We do have a reactive society and that drives the funding too,” he said. But he also sees some trending back toward proactive food protection, as companies see the economic devastation of even non-intentional contamination and realize they need to actively protect their brand and market share, he said. “Industry has been reawakened in regard to the concerns.”

A SHIFTING FOCUS. In addition, Mather said, the focus of food defense is shifting. Originally defense focused primarily on the potential of chemical contamination. While this is still to be guarded against, the primary concern has shifted to food ingredients, such as the melamine incidents of 2007. “This is another whole wave of concern, not necessarily by terrorists, but it certainly is intentional,” he said.

And it is a concern that requires an approach based on potential contaminating agents and their specific characteristics, said Faye Feldstein, acting director of the FDA/CFSAN office of food defense, communication and emergency response, in a session at the 2007 International Association of Food Protection Conference in Orlando, Fla.

The primary question that needs to be answered, Feldstein said, is “What happens to agent X in food Y?” It also is critical to understand how the agent affects a person who consumes the food and the dose at which harm is effected. Once these vulnerabilities are identified, mitigation strategies need to be determined and implemented, she said. “What can we do to help mitigate it if the agent was introduced?” Feldstein asked.

Shaun Kennedy, director of the National Center for Food Protection and Defense (NCFPD), also spoke during the IAFP session, describing the challenges the industry faces, particularly in relation to the complexity of the food chain and the lack of knowledge in the range of possible agents and their interaction in various foods. Thus, food protection, he said, should utilize a variety of detection system approaches including:

- detect to prevent — implemented at the site level where the contaminant could be introduced;

- detect to protect — implemented at the system level to halt consequences of contamination;

- detect to recover — emergency responsive action should a contaminant not be detected prior to distribution.

The challenge with any detection is the time lag that currently takes place, Kennedy said. Using the 2006 spinach E. coli contamination as an example, he said that although contamination was traced to August 15 and the first case determined to be August 19, the first announcement did not go out until September 14. “Some of the research we (at NCFPD) are doing is in trying to move back this curve,” he said.

DEVELOPING A PLAN. No matter what type of contamination or agent a plant is defending against, a well-developed defense program is very similar to a HACCP program, both Reeve and Mather agree, but the defense plan is focused on intentional sabotage rather than accidental contamination. Mather notes this same similarity of focus in FDA’s Food Protection Plan, published in late 2007. Not only does the plan apply to both food safety and defense, he said, it also applies to food for both people and animals, and food that is processed both domestically and internationally. “It points out the merging of these issues and, perhaps, the cloudiness,” he said. “The whole concern of food defense was necessary to address that as a specific item.”

When a plant begins to develop its plan, Reeve said, “The first thing that needs to happen is to conduct a vulnerability assessment.” Just as hazards need to be identified in order to set HACCP critical control points, a plant’s vulnerabilities need to be identified in order to set defense measures. “You can’t develop a hazard program without originating hazard analysis to find reasonable risk.

“The risk of not doing a vulnerability assessment is that you have lots of stand-alone sections,” he said. Too often, plants develop defense programs by simply pulling together various elements and calling it a plan, rather than basing the program on real guidance as to why the elements are important and how they work together for defense.

To create an effective plan for each area of your plant and the plant as a whole, “you need to determine your specific vulnerabilities,” Reeve said. Thus, just as with the HACCP plan, development of a defense program follows three basic steps:

- Identify the hazards or vulnerabilities.

- Identify the risks associated with each.

- Determine and develop countermeasures for defense.

“It’s similar to HACCP, but you are looking at it from a different angle,” Reeve said.

CONCENTRIC CIRCLES OF SECURITY. One way AIB describes this cohesiveness is as concentric circles of security — or layered security — working from the outside in. This can be literally walked through to determine existing security. For example, to ensure your electronic security system is completely protected, begin outside your building; are there any unprotected entrances? Next, enter the building; can someone get through the facility without being seen or questioned by an employee? Then enter the room where the security system is located; if a person were to get this far (or if a disgruntled employee were so inclined), could he or she get into the room? Finally, check the security system itself; is it password or code protected? Could it be manually turned off or over-ridden? Could it be otherwise disengaged? And — what countermeasures can be set up at each point to defend against threats?

While the outer circles of this security guard against external threats, the inner circles can help protect against internal acts, which often have higher occurrence rates. “Each organization does experience some level of internal intentional contamination,” Reeve said. Such acts are not even necessarily done to hurt consumers, but sometimes just to get attention, he added, citing an incident where an employee purposely put a dust pan in an ingredient bag.

To help reduce or prevent internal threats:

- Review all consumer and customer complaints, looking at those that could have potential to have been intentionally compromised, and review records for trends.

- Implement a workplace violence prevention program and, again, review records regularly for trends.

- Train supervisors and managers in employee relations, to help better minimize conflict.

- Provide employee awareness training so each employee understands his or her individual role and responsibility in the security of the plant and its food.

TOOLS, TRAINING AND EDUCATION. Although the industry still tends to be somewhat reactive in nature, it has produced a wide range of training documents and tools to assist food processors in their defense planning and assessment.

Additionally, this education is extending beyond the industry itself to include new college degrees and forms of training. Universities currently have courses and programs that focus on food safety, but no degrees and few programs or courses focused specifically on food defense or security, Mather said. MSU is one of the few universities that have developed a graduate program focused on food protection with a number of courses devoted specifically to food defense.

But the real key to continuing the expansion of knowledge is reiterated numerous times in FDA’s Food Protection Plan: a partnering between all applicable sectors.

“There’s a tremendous amount of information available in the industry that’s not always shared with regulatory agencies,” Mather said. “How much more would there be if there were more partnering?”

The author is Staff Editor of QA magazine.

Creating a Food Defense Plan

Shaun Kennedy, director of the National Center for Food Protection and Defense (NCFPD), said food protection should utilize a variety of detection system approaches, including:

- detect to prevent — implemented at the site level where the contaminant could be introduced;

- detect to protect — implemented at the system level to halt consequences of contamination;

- detect to recover — emergency responsive action should a contaminant not be detected prior to distribution.

To create an effective plan for each area of your plant and the plant as a whole, “you need to determine your specific vulnerabilities,” said Lance Reeve, director of food defense for AIB. Thus, just as with the HACCP plan, development of a defense program follows three basic steps:

- Identify the hazards or vulnerabilities.

- Identify the risks associated with each.

- Determine and develop countermeasures for defense.

“It’s similar to HACCP, but you are looking at it from a different angle,” Reeve said.

Explore the January 2008 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

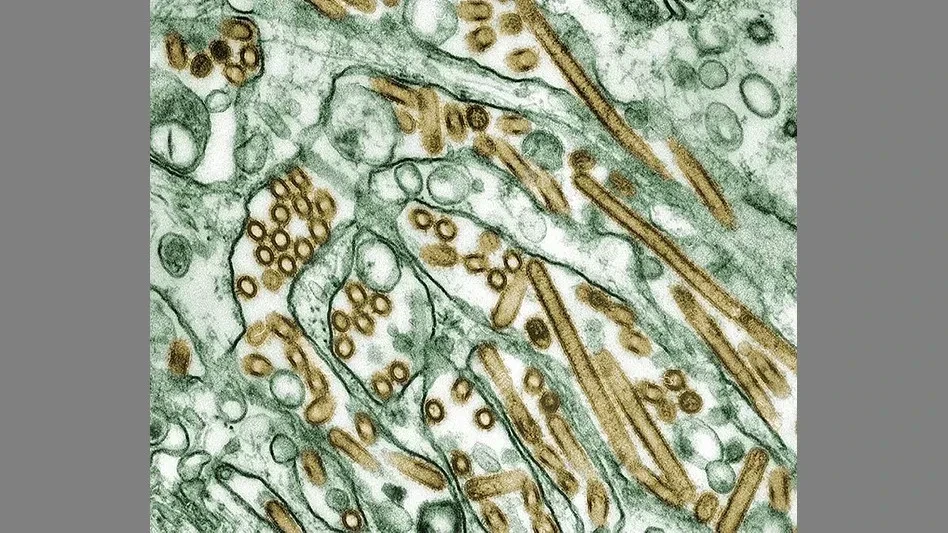

- USDA Invests Up To $1 Billion to Combat Avian Flu, Reduce Egg Prices

- Washington Cats Confirmed with HPAI as Investigation into Contaminated Pet Food Continues

- USDA Confirms Bird Flu Detected in Rats in Riverside

- Kyle Diamantas Named FDA’s Acting Deputy Commissioner for Human Foods

- QA Exclusive: Food Safety Leaders React to Jim Jones’ Departure, FDA Layoffs

- Water Mission Wraps Up Ukraine Response, Transitions to Long-Term Solution

- APM Steam Aims to Support Facility Preparedness for Winter with Steam Trap Surveys

- Therapy Helps Peanut-Allergic Kids Tolerate Tablespoons of Peanut Butter