A customer called to report a mouse found in the flour tailings from the morning production. “I need investigative help because we are placing suspect product on hold,” he said. The response: “We will have someone there today and at the originating flour mill for a precautionary investigation.” A mouse in flour. How did that happen?

Although this incident may be fictitious with any similarity to real events coincidental, there are lessons to be learned: Where is the food safety gap? How much did this incident cost? What are practical solutions to prevent an incident happening to you?

A sanitarian was at the frozen foods plant in a few hours. The mouse was validated and plans made to empty and clean the flour bin. Flour samples were obtained along with tailings records, receiving information, and driver and trucking company contact. No rodent activity was observed in the mill, and this was validated by the pest management records. Loading inspection and seals records were also in order.

The Investigation started with the mouse and the flour tailings container. The mouse was intact with evidence of a recent death, fresh blood, and no droppings. The tailings container was a plastic bucket with no lid. Two exterior multiple-catch rodent devices near an entry door had evidence of rodent activity (hairs). The pest management records indicated recent activity in the devices and noted a poorly sealed door. During the visit it was also observed that a labor dispute was underway.

The Cause was theorized to be a disgruntled employee who sabotaged the tailings by placing a dead mouse there, which was sourced from one of the nearby rodent devices. This was validated by a security camera.

Lessons Learned. Such critical food safety check points must be better secured to prevent such sabotage, and facilities need to be alert to situations that could affect quality assurance or food safety. In this case, the plant labor dispute created an atypical stressful work environment. The entry-door security camera identified the guilty employee, who was terminated. Consider, as well, other situations that could affect quality assurance and food safety, such as unusual weather conditions, nearby equipment installations, in-process cleaning activity, and a large-order rush. As you Manage By Walking Around (MBWA), be alert to situations outside the normal day-to-day activity.

Another lesson learned was the general lack of food safety in this area. Floor sweepings could have found their way into the tailings container. A better-designed container was installed with a locked cover accessible only by key. All other tailings-collection containers were modified as well. The nearby door was repaired, a simple but important task as pest management records indicated an ongoing rodent problem with this poorly sealed door. Food safety-related work orders should have top priority.

How much did this cost? Some direct costs were loss of flour, hours to clean bins, production downtime, and loss of an employee. Other direct costs were investigation time and expenses, hiring and training a new employee, and significant intangible costs. However, it could have been worse.

Conclusion. A mouse in flour may lead to a quick—but potentially incorrect—conclusion. Making decisions can be difficult but decisions are easier if you have the facts. Getting the facts is the hard part. When jumping to a conclusion, as is human nature, pause to see if you have the facts. Do the facts merit your quick conclusion? We can not know when the unusual will happen, but we must know how to respond when it does.

Explore the June 2012 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- Nestlé Opens Arizona Beverage Factory and Distribution Center

- Ingredion Invests $100 Million in Indianapolis Plant to Improve Efficiency, Enable Texture Solutions Growth

- Eagle Unveils Redesigned Pipeline X-ray System

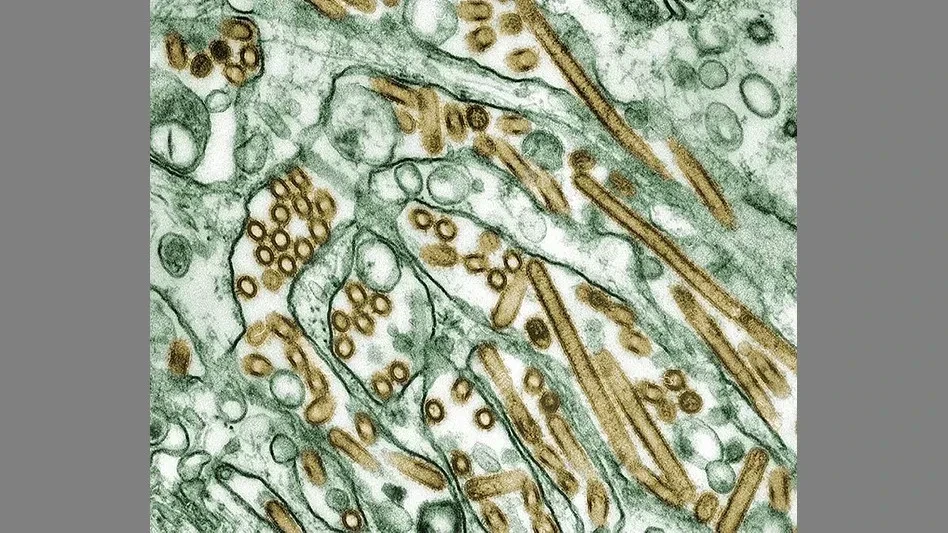

- USDA Invests Up To $1 Billion to Combat Avian Flu, Reduce Egg Prices

- Washington Cats Confirmed with HPAI as Investigation into Contaminated Pet Food Continues

- USDA Confirms Bird Flu Detected in Rats in Riverside

- Kyle Diamantas Named FDA’s Acting Deputy Commissioner for Human Foods

- QA Exclusive: Food Safety Leaders React to Jim Jones’ Departure, FDA Layoffs