Properly and effectively preparing and managing a sanitation program involves an organized process. Following are eight steps to success:

1. Prepare and document the program. Safety always should be paramount: personnel trained and properly supervised to use correct personal protective equipment, and have access to all MSDS information. The program should be documented and describe cleaning and sanitation procedures for all equipment, including critical or complex tasks as well as limitations and considerations relating to sanitizer usage. The documented program should be stored in a convenient place for sanitarian review. A schedule of all equipment and areas to be cleaned and sanitized, should be detailed, including specific cleaning and sanitizing tasks for each area. Roles and responsibilities should be clearly allocated for overall and day-to-day management of the program, including the frequency of cleaning and person(s) responsible for each task.

2. Identify the process flow, cleaning strategy, and cleaning process for each specific processing environment. A poorly designed process could result in cross contamination of equipment and surfaces. Where food production requires a wet cleaning, follow a typical schedule of initial dry clean to remove gross soils, a rinse to remove the remaining soil, then a visual inspection of the area. Soaping and scouring with appropriate detergent should be followed by a rinse and inspection. Disassembled parts should undergo a pre-operational inspection before reassembly, and all tools and hoses should be removed from the production room. Finally, appropriate sanitizer should be applied while equipment is running to ensure adequate distribution. Some production lines may have specific cleaning and sanitizing requirements, such as dicer blade removal and cleaning, and these should be clearly defined.

3. Review equipment construction and its composition. To prevent damage to sensitive surfaces and ensure that all difficult-to-clean areas are addressed, all equipment should be reviewed, with a focus on the construction and composition. Stainless steel is preferred and is often specified. Aluminum is of special concern because it can be attacked by acids and alkaline cleaners. These types of compounds can cause darkening and corrosion and can dissolve aluminum quite rapidly. Non-metallic surfaces such as plastics are becoming more prevalent in some industries. Plastic challenges finclude stress cracking and clouding when cleaning products intended for other surfaces are used.

4. Carefully consider the suitability of cleaning and sanitizing agents. Use only chemicals suitable for use in food-producing operations. Consider the type and nature of soil and whether particular areas of the production environment are prone to invisible soil such as microorganisms. The application method for cleaning products should be stipulated to protect the sanitarian and to provide optimal coverage for each application. A documented cleaning and sanitizing program should ensure that parameters are clearly outlined. The program may describe pH limits, temperature limits, concentration ranges, and exposure times. Documenting these helps ensure that correct quantities of chemicals are used and the desired effect is achieved.

5. Consider the quality of the water supply. Water hardness is considered one of the most important chemical properties of water and excessive hardness may form scale or leave films that can hinder the action of cleaning agents. Softening is sometimes required; increasing concentration of detergents may work but it also will increase use of cleaners. Acid or alkaline cleaners are generally not affected by water pH as these compounds have an element of buffering capacity; however pH may affect sanitizer efficacy, for example sanitizers with optimum efficacy at acidic pH may lose some effectiveness if prepared in highly alkaline water.

6. Support the program. The effectiveness of a sanitation program can be verified in different ways and, often, a combination of approaches should be used. Visual inspection such as closely examining cleaned surfaces for visible soil, tracking chemical use, monitoring records, and reviewing cleaning charts can be very useful in determining whether program compliance has been achieved. Other more specific methods include rapid sanitation tests, such as ATP swabs, and testing surfaces for microbial contamination using standard microbiological culture techniques. Each of these methods varies by cost, timeliness of results, and level of technical expertise needed. To provide value, they need to be conducted regularly over time so trends can be tracked. You also need to have a plan to address corrective action.

7. Train and retrain. The sanitation program should be viewed as a process of continual development, revisited constantly, and updated to accommodate new cleaning technologies, products, and tools. When changes occur, employees should be promptly trained in the newly revised cleaning methods.

8. Ensure management participation, accountability, and commitment. As a final note, sanitation programs will only be successful if they have the full commitment of all employees, including executives, managers, and supervisors. Without this commitment the plan will inevitably fall short of its intended purpose.

Explore the June 2013 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- Eagle Unveils Redesigned Pipeline X-ray System

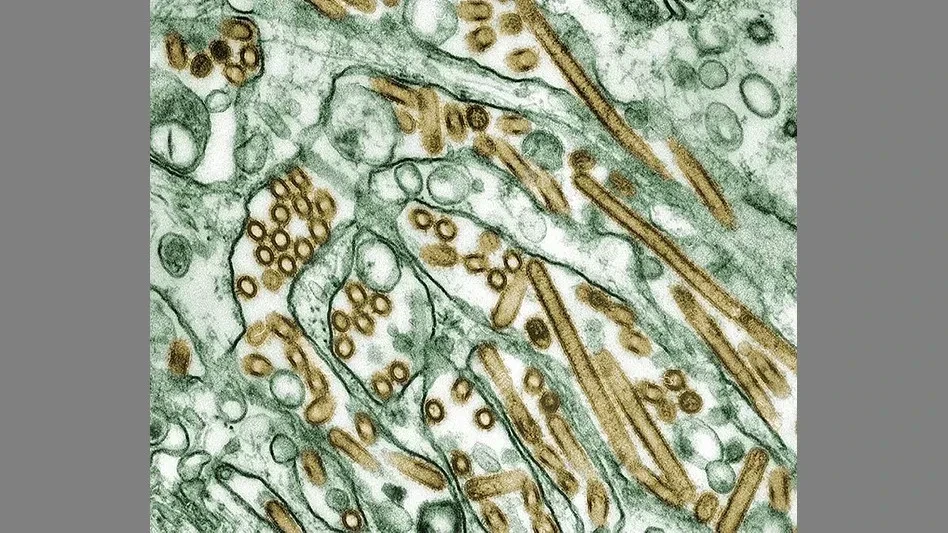

- USDA Invests Up To $1 Billion to Combat Avian Flu, Reduce Egg Prices

- Washington Cats Confirmed with HPAI as Investigation into Contaminated Pet Food Continues

- USDA Confirms Bird Flu Detected in Rats in Riverside

- Kyle Diamantas Named FDA’s Acting Deputy Commissioner for Human Foods

- QA Exclusive: Food Safety Leaders React to Jim Jones’ Departure, FDA Layoffs

- Water Mission Wraps Up Ukraine Response, Transitions to Long-Term Solution

- APM Steam Aims to Support Facility Preparedness for Winter with Steam Trap Surveys