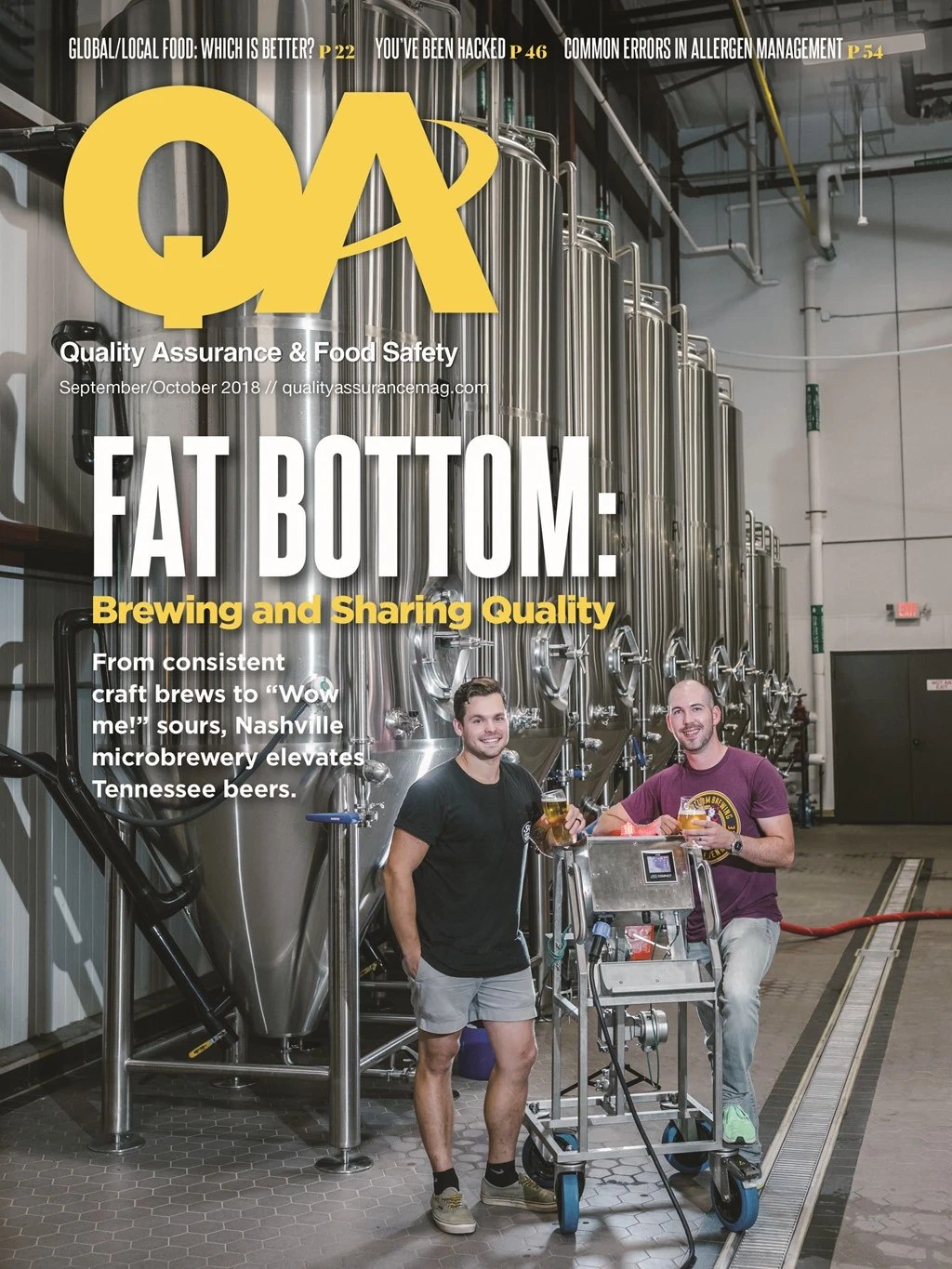

Photos by Jason Bihler

Granddad’s PJs. Ruby. Two-Piece. Pepper Pale. Not exactly terms you would associate with a Brown University computer science grad, but certainly applicable to one who gave his notice at the software company to turn his homebrewing hobby into a microbrewery business. Why? “I decided beer would make me happy,” said Nashville’s Fat Bottom Brewing Co. Founder and Owner Ben Bredesen. “And the science is the same whether you are brewing five gallons or 500,” he said.

So in 2012, Bredesen opened his first brewery in a 5,000-square-foot building in East Nashville “on a shoestring budget.” But within two years, the business was already outgrowing the space, and Bredesen was wanting to add packaging operations in addition to their draught beer sold on-site. Having also been doing all the brewing, sales, and business management himself, he said, “I realized pretty quickly I couldn’t do it all.”

So he hired Brewmaster Drew Yeager, who is now both brewmaster and director of brewery operations. “Drew was my first really significant hire,” Bredesen said, and he was hired because of his passion for beer and brewing. “We are all here because we love beer,” Bredesen said. Then when the opportunity came along to purchase an acre and a half of land in West Nashville, Bredesen decided it would be a great fit for a new state-of-the-art facility which would enable growth.

It took nearly a year to build out the new 33,000-square-foot facility, which included an 18,000-square-foot brewing and packaging space; a modern, well-equipped quality lab; and a bar restaurant with separate event space and an outdoor patio/game area. The bar itself went from six taps to 20 taps, 17 of which are dedicated, and “we can experiment on the others,” Bredesen said. Although the space was bigger than needed at the time, it would not only allow for expansion, it would enable the production area and restaurant to be in the same building. This was important to Bredesen because, he said, “We wanted our customers and retailers to come to the restaurant and also see the brewery.”

THE BEERS. Today, Fat Bottom produces 28 beers, of which four are its flagships: W.A.C. Pale Ale, Ruby Red Ale, Knockout IPA, and Ida Golden Ale. Some are seasonal or on-tap-only beers and a couple are the brewery’s new sour/barrel-aged beers.

When the new facility was built, a separate 3,000-square-foot sour room was included. “Sour beers are purposely infected with wild yeast or bacteria, and we don’t want that in the clean room,” Yeager said. Sour beers are, in fact, a return to the days before refrigeration and fermentation technologies, when naturally occurring wild yeast strains and bacteria were intentionally allowed in the brew. It is these that give the beer acidity which imparts its complex, sour taste. Thus, “the sour room is negative pressure to keep the ‘bugs’ in,” Yeager said. “Anything that lives in there stays in there, and everything is color coded.”

A key difference between sour beers and the other craft brews are the sours’ lack of consistency. “A sour will keep changing,” Yeager said. “It will have a consistent essence, but the taste can be different. Like wine, sour beer has a ‘vintage.’”

But, he added, “That’s the one part of the business that doesn’t have to be consistent. One of the hardest parts about brewing pilsner or golden ale is being consistent.” But it is just those diverse characteristics that make a brewery special. “I like to see a brewery that does both,” Yeager said. “Having a stylistic, clean, consistent brand and having a ‘Wow me!’ beer.”

THE PROCESS. Whether creating a clean, consistent beer or a “Wow me!” beer, it all starts in the base silo. Fat Bottom uses two-row malt which has lower enzyme and greater starch content enabling higher production and, generally, a mellower flavor than six-row malt. To get to the starch content, the malt is milled to a crush. “The more rolls you have, the better you can dictate your crush, and you want to create as much surface area as possible without shearing the husk,” Yeager said. So the brewery uses a four-roller mill: the first set keeps the husk intact; the second set further crushes the endosperm to increase the surface area and access the starch.

A chain and disk auger then carries the crush to a mash tun where it is mixed with water at the proper strike temperature then allowed to rest for 30 minutes. This rest period allows the natural enzymes to convert the starch to sugar. The vorlaufing (recirculating) of the mash in a lauter tun then clarifies the wort and sets the filter bed. The wort is fed by gravity to an external vat, then pumped to a kettle where it is boiled and sterilized for one to two hours depending on the style of beer being brewed. Any hot-side ingredients are added at this stage.

The next step is the feeding of the wort into a whirlpool, where any proteins, trub (sediment), and denser solids are sucked down to the bottom, leaving a clear liquid. This is then pumped through a heat exchanger which drops the temperature to 65°F. Once cooled, it is ready to be fermented through the addition of a perfect pitch of yeast. If too much yeast is used, off flavors will develop; if too little, the fermentation may not finish.

Proper tending of the equipment also is important for worker safety. During fermentation carbon dioxide is produced. To enable the tank to release the CO2 and relieve the built-up pressure, each tank has arms at the top to which stainless steel blow-offs are connected; the blow-offs drop down into buckets of water to create an airlock and keep the fermenting beer from being exposed to the outside environment.

Fermentation generally takes five to seven days, though low gravity beers ferment in about three days and lager in 14. After fermentation, tank temperature is reduced to 32°F; remaining yeast or trub is purged two or three times; and the beer is filtered in a centrifuge. “Every beer we make goes through our centrifuge,” Yeager said. “I believe you drink with your eyes first, and beers should be clear, not hazy.” In addition to the aesthetics of it, the hazier the beer, the less stable it is, he said. Most of Fat Bottom’s beers also are run through a polishing filter to further clarify them, then each flows into a brite tank to be carbonated.

While Fat Bottom has a number of computerized systems, none are automated to correct themselves, Yeager said, explaining, “We’re the ones making the beer.” Despite what may sound like a somewhat complex, jargon-laden process, “all we really are is yeast farmers,” Yeager said. “We’re just lucky that the byproduct is what we sell.”

QUALITY SHARING. As was the case when Bredesen founded Fat Bottom, start-up microbreweries can’t always afford the capital investment that a lab requires. But maintaining quality, safety, and consistency of the brews is difficult, if not impossible, without at least some lab equipment.

It is for just that reason that Fat Bottom not only invested a great deal in the lab of its new facility, it also is investing in Tennessee beers by allowing other breweries in the state to use its equipment. “Anything we do here we offer to any Tennessee brewery,” Yeager said. “If we can help any beer in Tennessee do better, we help all beers in Tennessee.”

Not only does that keep the reputation of the state’s beers and breweries at a higher level, it’s good to build relationships between brewers, Yeager said. “We’re all doing the same thing, we just do it differently.”

When conducting tests for other breweries, Quality Assurance Lab Manager Alex Barr provides an analysis of the results, and recommendations. “Sometimes there are results I don’t want to deliver, but I explain options to try to solve the issue,” he said.

Among the quality and food safety tests conducted in the lab are checks for bacteria; dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide — down to parts per billion; gravities —the amount of fermentable sugars during brewing and in the finished beer; IBU for bitterness; color; and seams, Barr explained.

Because the formation of the seam is so critical, Fat Bottom invested in a video microscope through which the seams are analyzed. “It shows if the seams are tight and not losing CO2 or product,” Barr said. Prior to the brewery’s purchase of this equipment, “I had personally gone through an entire pallet of beer looking for a leak,” he said.

Like most food and beverage producers, the brewery also uses sensory panels for quality. But Fat Bottom adds an extra spin to its panels — using the Draught Lab app. Through the app, which can be run from a smartphone, a brewery builds flavor profiles against which it can test and troubleshoot its beers in an objective and structured way. “They developed a way to make sensory testing user friendly,” Barr said.

“We try to work on continual improvement,” Yeager said. “There’s always something you can do better.” And the striving for improvement seems to be working as it has won numerous national and global awards such as its two 2018 World Beer Cup awards including Silver for The Baroness beer and Bronze for Wallflower Spring Saison and eight 2018, four 2017, and four 2016 Tennessee Championship of Beers awards.

WORKER PASSION. Awards are a significant validation of a company’s quality. But, Yeager said, “It’s not only about getting drinkers to drink beer and enjoy it, it’s about understanding the culture of the company.” As an example, he said, when two restaurant owners came to visit the facility, they were interested not only in what Fat Bottom was doing, but also, “who we are and why we do what we do,” Yeager said. “It’s why you have to be so selective about who you hire.” And once hired, he added, “You need to find ways to engage your staff because they have an impact on the outcome.”

It is for this reason that building a culture of quality and safety, as well as community service, is so important at Fat Bottom; and it is an initiative that resonates with the young people who drive retail sales, he said. “Engaging them in the company’s culture is one of the best things a brand can do right now.”

One charitable promotion which the brewery created this year — and intends to make an annual initiative — is Collaboration Nation. Conducted in conjunction with the Craft Brewers Conference which was in Nashville this year, Fat Bottom hosted the collaboration event which features limited-edition beers from participating breweries, with a portion of each beer’s proceeds going to a charity of each brewery’s choice. That type of partnering is common among brewers and one reason Yeager is in brewing, he said. “I wanted a project to celebrate the reasons I got into the business: fun, good beer; relationships; and laid-back people.”

But to ensure quality, it can’t all be fun and laid back, of course. One of the areas that Yeager focuses on with Fat Bottom employees is an honest look at each person’s weaknesses, what they want to get better at, and what they need to do to get better. “Always use your weakness as your strength,” he tells them. For example, if your greatest weakness is inexperience, then your greatest strength is that you have no bad habits formed. It also will mean, however, that you may have to work harder than another employee to learn and grow. Additionally, Yeager meets with each member of his team biweekly, monthly, quarterly, and annually to set and review goals that will meet the needs and objectives of both the worker and the company. Sometimes it’s a matter of finding ways to help workers stay engaged when doing repetitive tasks and mundane aspects of their jobs. “The better they do, the better we are as a company,” he said.

Yeager sees three key reasons why workers may not perform to a quality level:

- Lack of education: If they don’t know it’s wrong, how do they know when it’s right?

- Lack of equipment/tools: If they don’t have the needed tool, how do they perform the task effectively?

- Lack of desire: If they don’t care, they won’t do what’s needed.

Keeping workers focused on the task at hand also means ensuring the environment is comfortable for them. Although the production areas of the microbrewery are not air conditioned, primarily because of the heat and the CO2 that can build up in the brewing process, the areas are kept at a relatively comfortable temperature. This is enabled through the installation of industrial ceiling fans which circulate the air and exhaust the CO2 out of the building. The fans also help with evaporation of the moisture in the plant to keep bacteria from building up in those areas. “Our drainage is very good, but water dries even more quickly when the air is moving,” Yeager said.

Additionally, he said, “We’re making so much heat in so many areas, but it’s important for things to be hot where they’re supposed to be hot.” Thus, the fans also help to keep workers cooler without the excessive cooling of equipment that could be caused by air conditioning. Additionally, Yeager said, “Whenever the tanks are opened under positive pressure, the Hunter fans are turned off in those areas.” This is enabled by the independent control of each fan. Having a cool environment is important for employee comfort, but also for their safety, he said. “If they don’t enjoy what they’re doing or they’re tired or dehydrated, that’s when mistakes can happen.”

INTO THE FUTURE. About half the brewery’s volume is served on draught on-site or through distribution. The other half is canned or bottled and distributed to stores throughout Tennessee and parts of Alabama, and the company is looking to further increase that distribution. The beer is currently processed in two rows of tanks and there is space for four more rows, which Yeager says would be 120-barrel tanks — twice the size of the largest ones it has today.

But even with that space to grow, Bredesen said, “Someday I would like to have a 200,000-square-foot brewery.” With this computer scientist already having grown from homebrewer to award-winning, 34,000-square-foot, 6,500-barrel-a-year microbrewery in less than six years, that goal is likely not far down the road.

The author is Editor of QA magazine. She can be reached at llupo@gie.net.

Explore the October 2018 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- Bird Flu: What FSQA Professionals Need to Know

- Registration Open for 129th AFDO Annual Educational Conference

- Frank Yiannas, Aquatiq Partner to Expand Global Reach of Food Safety Culture

- World Food Safety Day 2025 Theme: Science in Action

- Ancera Launches Poultry Analytics System

- USDA Terminates Two Longstanding Food Safety Advisory Committees

- Catalyst Food Leaders Announces Virtual Leadership Summit for People in Food

- Food Safety Latam Summit 2025 Set for Mexico City