All photos courtesy Association for Food and Drug Officials

Editor’s Note: This story is part of a partnership between the Association for Food and Drug Officials (AFDO) and QA magazine. For more information on AFDO, please visit afdo.org.

The author, Joseph Corby worked for the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets for 37 years, retiring in 2008 as the Director of the Division of Food Safety and Inspection. He served over 10 years as the Executive Director for the Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO), retiring in October 2018. He has been an outspoken advocate for the advancement of a nationally integrated food safety system and continues to work with numerous groups and associations in support of this cause.

Later this year, QA will partner with AFDO on a series of webinars that will dig even further into the attempt to develop a nationally integrated food safety system.

It is said that great ideas develop through human interaction and debate. As those ideas evolve, there will most likely be argument and conflict to contend with. Some ideas form when brainstorming over a cup of coffee or, in some circles, during an evening at a tavern. That’s where the idea of creating a nationally integrated food safety system began — at a lounge called Studebaker’s in Rockville, Md., 25 years ago.

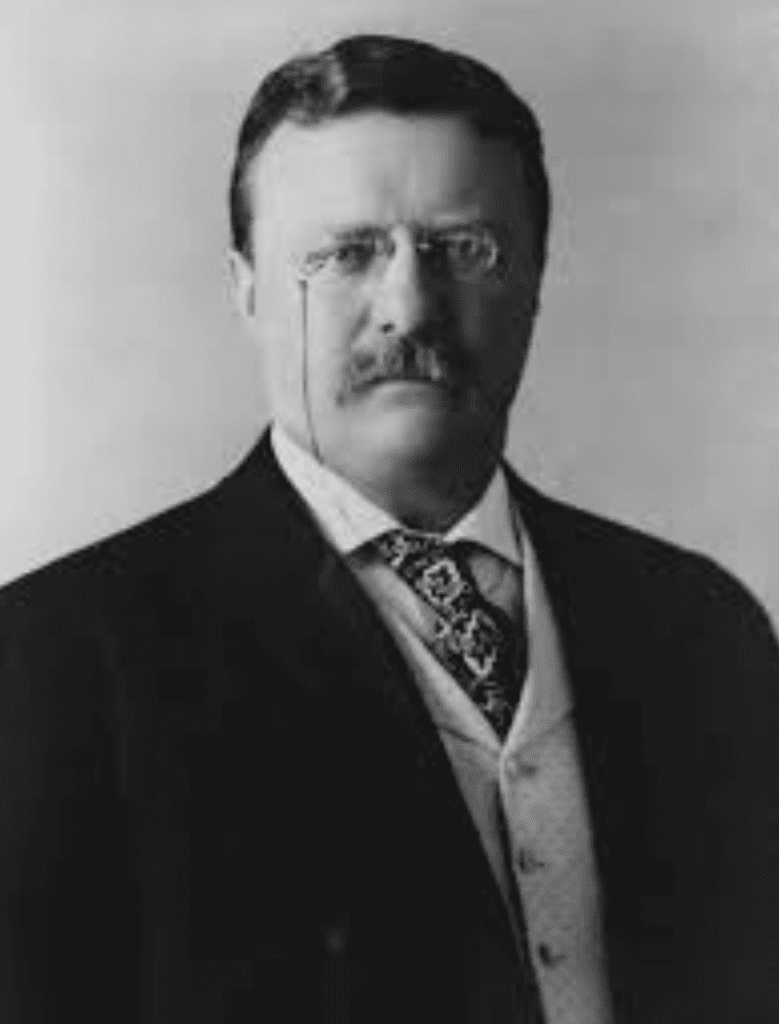

Twenty-five years may seem like a lifetime to many, but in government circles, it’s not that long. For instance, Peter Collier was chief chemist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1880 when, following his investigations into food adulteration, he recommended passage of a national food and drug law. His bill was defeated. During the next 25 years, more than 100 food and drug bills were introduced in Congress. Finally, in 1906, the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt (Fig. 1).

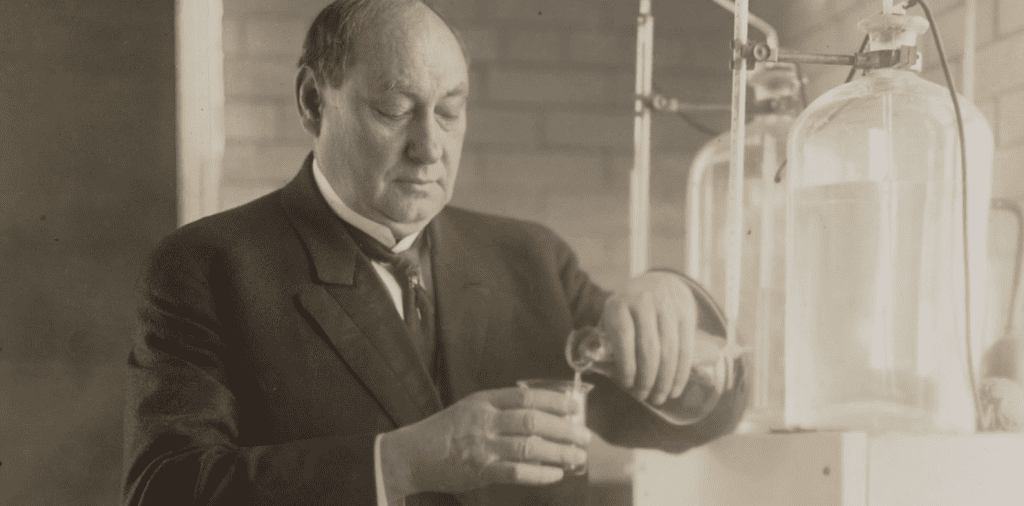

During that time span, efforts by determined women’s clubs, state officials, and a very bold USDA Chief Chemist named Harvey W. Wiley (Fig. 2) influenced the eventual passage of the new food and drug law. Remember that during this 25-year effort, Wiley had to poison 12 volunteers (the Poison Squad) (Fig. 3) to help influence the law’s passage. Patience is an absolute quality of food protection officials.

The engines for government change take time, yet change must persist if we wish to influence our desired outcomes. Tangible momentum is a powerful thing, and fortunately, there are many examples we can refer to in our efforts to create a fully integrated food safety system. Initiating change that involves altering government agency culture is a tough business; building momentum is fundamental to accomplishing the goal. The momentum we’ve achieved through so many important projects and efforts keeps the vision of an integrated food safety system ongoing. Rather than being discouraged, we should be encouraged by what we’ve accomplished in those 25 years.

EARLY YEARS. In 1939, AFDO Vice President Commissioner E. G. Woodward (Fig. 4) wrote an editorial in AFDO’s Quarterly Bulletin about an integrated food safety system: “The greatest single program of work before the Association is to follow through with its efforts for uniformity in state legislation until this whole nation has an integrated system of similar Food, Drug and Cosmetic Laws, interpreted, administered, and enforced in a single spirit of uniformity.”

That may have been the first time the words “integrated system” were ever mentioned by anyone associated with AFDO. The organization was established to address uniformity of state legislation and rulings, not to coordinate resources and activities with federal agencies. After all, there was no FDA when AFDO was originated.

As the years passed, AFDO offered advice to federal agencies about what they should do to improve federal-state relations. Actually, those recommendations were quite successful: They were persuaded to create an Office of State Cooperation, which eventually became the Division of Federal State Relations and is known today as the FDA Office of Partnerships. This is where many of FDA’s integration efforts would happen.

Many early leaders and pioneers for food safety participated in AFDO conferences. It always impressed me that Wiley, the “father” of food and drug law, was an active participant in the organization and relied on our state officials to help advance his causes, which included the adoption of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act. In 1906, he spoke at our annual association meeting in Hartford, Conn., just 2½ weeks after the law was enacted. He thanked the members of AFDO who worked to accomplish the national rule.

Here is what Wiley said: “The people of this country, it seems to me, are to be congratulated upon the splendid work which has been accomplished by the national legislature. While no one claims that the law … is a perfect one, yet everyone will admit that it is based on sound principles of ethics and justice. If experience shall show that it is weak in any of its provisions, the attitude of the national Congress is … that any needed amendments can be easily secured. This meeting, therefore, takes place under what may be considered most favorable auspices respecting the legislative aspects of the pure food question.”

After the new law was enacted, AFDO continued to devote its mission to uniformity among the states, which was considered important and something very much desired by industry. However, state and local agencies continued to promulgate their own rules, which they believed were important to the citizens they served. To many, it seemed that the only way to create uniformity was to legislate it in federal law. This idea was not well accepted by AFDO or state and local governments. However, a new idea and vision arose that became AFDO’s ongoing focus.

THE IFSS VISION. It is Dan Smyly, the former Director, Division of Food Safety, Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services and President of AFDO (Fig. 5) from 1997 to 1998, who is credited with first formulating and advancing the vision of a nationally integrated food safety system. What he started on his own has resonated for 25 years, and it is still a rallying cry of AFDO and many food protection officials.

Shortly after he became AFDO President in June 1997, food law attorney George Burditt asked him to participate on a panel at the Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society (RAPS) Conference on Sept. 9, 1997, in Washington, D.C., to discuss "Regulatory Cooperation over the Next Five Years." This seemed timely, since the U.S. Congress was then debating plans to balance the federal budget, which generally meant funding for the states would become tight.

On his flight to the RAPS Conference, he reflected on all the complaints he’d received at the Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services from state legislators and business owners concerning the number of different agency inspectors coming into businesses to perform inspections and investigations. He jotted down some notes to eliminate duplication of the regulatory activities provided by federal, state, and local agencies and to develop a nationally integrated system for food safety.

During the RAPS panel discussion, Smyly made the following comments: “With the dwindling resources available for government services and with the current taxpayer attitude of no new taxes, no increases in user fees and reduction in regulations, it is critical that government at all levels develop effective ways to pool all available resources and to work smarter and more cooperatively in regulating food. All major stakeholders at the federal-state-industry regulatory interface must continue to work toward the development of a truly Vertically Integrated National System [VINS] for regulating food. In some quarters, this may be referred to as ‘seamless regulations.’ By properly inserting a good word starting with ‘e,’ we could call this system ‘VINES.’ Through continued communications, we must sort through all activities or functions needed to establish the most effective nationally integrated regulatory system. We should then determine which level of government is best equipped to carry out each function and assure that adequate resources are provided at all levels of government to implement the system. The state and federal agencies have a long history of working together through various cooperative agreements, contracts, grants, memoranda of understanding and, most recently, partnerships. In my view, we must get beyond partnerships.”

At the fall AFDO Board of Directors Meeting in early November 1997 in Rockville, Smyly decided he should share his recent remarks at the RAPS Conference about his vision for a nationally integrated system for food safety. So, the evening before the board meeting, he discussed this topic with Dennis Baker from the Texas Department of Health (Fig. 6) while having a few drinks at Studebaker’s, a popular watering hole for board members when they were in town.

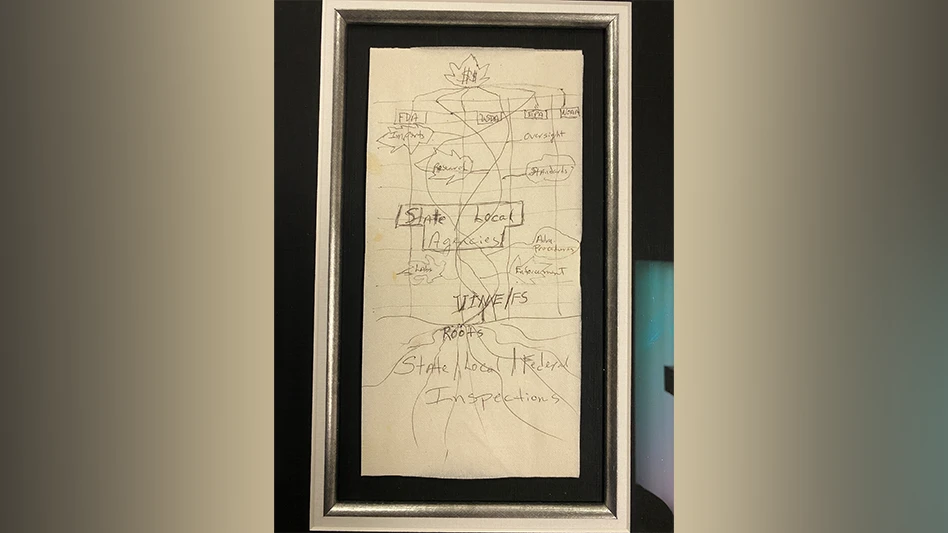

During this discussion, Smyly drew his vision on a cocktail napkin (Fig. 7), although it was very dark in the lounge. This may account for what appears to be a bit of scribbling on the napkin, but a few too many libations may have contributed to this as well.

Discussions continued late into the evening in the AFDO Presidential Suite with other board members, and they agreed to discuss this topic at the board meeting the next day. The AFDO board agreed that the vision for a nationally integrated system for food safety should be pursued and that support should be sought from the appropriate federal agencies to organize a national meeting to discuss the concept. Also during the board meeting, it was suggested that the word “enterprise” may be used for the letter ‘e,’ providing the desired acronym VINES (Vertically Integrated National Enterprise System), which the seamless regulatory system became known as.

Smyly followed up by writing letters to Michael Friedman, Lead Deputy Commissioner of the FDA, and to Catherine Woteki, Undersecretary for Food Safety with USDA. He requested their support to convene a “select group” to work with a facilitator to craft “the blueprint” for the future vertically integrated national food regulatory system. He received responses to his letters, but the agencies were cautiously awaiting the National Academy of Science (NAS) Committee report, "Ensuring Safe Food from Production to Consumption."

Later that month, Smyly gave an impromptu presentation at the Third Annual Federal/State Conference on Food Safety in Sacramento, Calif., on his thoughts and vision for a nationally integrated food safety system. He mentioned the long history of the states and federal agencies working together and stated the following:

“Most recently the buzzword is partnerships. Partnerships are certainly a central piece of the current strategy that we must use as we move from where we’ve been for the last several decades to where we ought to be in the very near future. Again, I think our dwindling resource base leaves us no option except to do that. And for us to have a truly national integrated food regulatory system, we must involve the president, Congress, governors, state legislators, and other state executive leaders to provide adequate resources at all levels of government to implement the national system.”

Smyly drew his vision on a cocktail napkin, although it was very dark in the lounge. This may account for what appears to be a bit of scribbling on the napkin, but a few too many libations may have contributed to this as well.

Key USDA personnel in attendance appeared to be on board regarding the concept. It was suggested that he contact the Committee Chair of the National Academy of Sciences Committee to Ensure Safe Food from Production to Consumption and request they hear from someone who could provide a state and local perspective. Smyly contacted Chairman John C. Bailar and was invited to participate in a State/Local Regulatory Panel at a NAS Committee Meeting on April 30, 1998. During the panel discussion, he clearly stated AFDO’s belief that the current concept of a “federal system” and a “state/local system” should be fundamentally changed to a “fully integrated national system.”

In its final report published in August 1998, the NAS Committee incorporated language related to the national integrated system concept, which may have helped push FDA to support it. The report recommended a “National Food Safety Plan” that should:

- Include a unified, science-based food safety mission

- Integrate federal, state, and local food safety activities

- Allocate funding for food safety in accordance with science-based assessments of risk and potential benefit

- Provide adequate and identifiable support for research and surveillance

- Increase monitoring and surveillance efforts to improve knowledge of the incidence, seriousness, and cause-effect relationships of foodborne disease and related hazards

- Address the additional and distinctive efforts required to ensure the safety of imported foods

- Recognize and provide support for the burdens imposed on state and local authorities that have primary front-line responsibility for the regulation of food service establishments

- Address consumers’ behavior related to safe food handling practices

Smyly met with FDA/CFSAN Director Joe Levitt (Fig. 8) and Deputy Director Janice Oliver in July 1998 to further discuss the concept and make plans for a 50-state meeting in September.

Smyly also met with AFDO Director of Public Policy Betsy Woodward and me to convert the integration vision into a written document. This was published in the AFDO Journal for September 1998 and included two schematics to clarify the vision and concept. The schematics addressed the food safety mechanisms and tools to be integrated. Both designs looked a little bit like the cocktail napkin prepared the previous year at Studebaker’s.

As fate would have it, Dan Smyly left state service for a job in the Scientific and Regulatory Affairs Department of the Coca-Cola Company, and the integrated food safety torch was passed to a new individual from AFDO ... That would be me!

EARLY HURDLES. Fortunately, AFDO was fully on board with this integration vision, and I had no problem getting support for the ideas I had for moving forward the Smyly vision. FDA Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) Director Joe Levitt was a very strong advocate of integration as well, so I thought, together, we could advance our ideas for change very quickly. Boy, was I wrong!

There were three huge hurdles in our way, which we learned very quickly.

The first? Consumer groups voicing their strong concern and disapproval of our integration concept. Actually, the consumer groups were not huge fans of state and local programs at the time. They believed state and local agencies should only be involved with the inspection of restaurants and grocery stores since these firms weren’t that complicated to regulate at the time. Consumer groups also were concerned that the economic interests of industry within states would be a source of conflict if states were to have an expanded food safety role that included activities thought of primarily as a federal responsibility.

I was very naïve at the time and felt like the meeting I had scheduled with all the consumer groups in Washington, D.C., would be a cakewalk. I assumed they’d love this idea of a national integrated system, so I decided to meet with all of them alone.

I walked into this meeting feeling very confident, and I walked out feeling dejected and discouraged. I was informed that consumer groups could never support an integrated system with the states unless there were program standards illustrating the equivalence of state and federal programs. After my blood stopped boiling, I began to think that maybe the consumer groups were correct to demand program standards. To this day, I credit Carol Tucker Foreman from the Consumer Federation of America, who was very outspoken and insistent on program standards. Today, we recognize program standards as the foundation for ensuring the success of an integrated food safety system.

Now, we have established regulatory program standards for manufactured foods, animal feed, retail food, shell eggs, and produce. Because of these standards, we can illustrate agency equivalence in all of these areas, and we are now able to establish mutual reliance and true partnership between government agencies at all levels.

The second and third hurdles dealt with trust and culture. There were not only issues between federal and state programs but also, in some instances, between state and local programs. We knew these hurdles would take time to resolve, but we believed open communication through the continuation of 50-state meetings and creation of the National Food Safety System (NFSS) project would help to improve these matters. Meetings and engagements provided a sense of human interaction, which helped to build trust and make it easier to form deeper connections that would lead to stronger relationships and a healthier, more coordinated food safety culture. We’ve made great strides in addressing trust, but we must continue to deal with differing agency cultures to ensure our behaviors and beliefs about food safety are comparable. Efforts here must continue so we may think more strategically.

While the first vision of an integrated food safety system began with the scribbling on a cocktail napkin, it was the National Food Safety System (NFSS) project where development and implementation began.

NATIONAL FOOD SAFETY SYSTEM PHASE ONE: CREATING THE VISION. The first 50-state meeting to work on developing the blueprint for the fully integrated national food safety system was held Sept. 15-17, 1998, in Kansas City. The theme of this meeting was “Meeting Challenges Together,” and it centered on the need for all levels of government to better utilize their resources in a coordinated fashion — from farm to table.

Attendees were asked to brainstorm their vision of a successful food safety system in the year 2005 and to identify obstacles to achieving this vision.

Interesting that their vision was much like the vision of Dan Smyly and the one we share today. It included the following:

- Creation of strong regulatory program standards

- Federal oversight

- Full information and data sharing

- Application of an effective and coordinated communication system

- Work planning to coordinate resources and avoid duplication

- Inspector competency through concentrated training and certification

- Credible and organized enforcement activity

- Uniformity of agency programs and laboratories

- Acceptance of state and local analytical data and information

- Greater responsiveness to outbreaks and recalls

- Improved public health surveillance

Here are some of the obstacles the NFSS attendees identified:

- Lack of trust

- Lack of commitment

- Lack of clearly defined roles and responsibilities

- Lack of uniformity

- Lack of industry and consumer support

- Legal issues that prohibit resource and information sharing

- Ineffective communications

- Inadequate funding

While the first vision of an integrated food safety system began with the scribbling on a cocktail napkin, it was the National Food Safety System (NFSS) project where development and implementation began.

I remember this meeting well, and the highlight of it, in my view, was an announcement that Dennis Baker from the Texas Department of Health was just appointed FDA’s Associate Commissioner for Regulatory Affairs (ACRA). As the AFDO President at the time, I told those in attendance how this appointment illustrated FDA’s commitment to the integration effort. I was a member of the FDA selection committee for the ACRA position, and while I fully supported Baker, I felt the job would go to one of the many FDA officials who had applied. So his appointment was a real milestone for our integration effort.

Baker would work with FDA Commissioner Jane Henney (Fig. 9) to advance an integrated system, and it quickly became clear that Commissioner Henney wanted to stay connected with state and local programs. She was fully aware of the relationships he’d made with state and local officials from around the country and through AFDO. Perhaps because of this, she obtained U.S. Senate approval to elevate Dennis Baker to the third-highest position in FDA.

Clearly, the most important outcome of this 50-state meeting was the early formation of the National Food Safety System (NFSS), the group that would formulate an integrated system. NFSS was a large group of federal, state, and local officials who volunteered to work through work groups to identify the necessary foundational elements needed to advance the concept. There were six work groups consisting of over 70 local, state, and federal officials. The work groups included:

- Roles and Responsibilities

- Coordinating Outbreak Responses and Investigations

- Information Sharing and Data Collection

- Communication

- Minimum Uniform Standards

- Laboratory Operations and Coordination

An 18-member Coordinating Committee also was formed of local, state, and federal officials to coordinate all the groups’ work.

Everything looked in order, and we were off on our journey to create an integrated food safety system.

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCE, 1998. While all these early NFSS activities were going on, the U.S. Congress commissioned the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) through the Agricultural Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to conduct a study to assess the effectiveness of the current food safety system. They were also asked to provide recommendations on scientific and organizational changes needed to increase the effectiveness of the country’s system. Their study resulted in a report entitled “Ensuring Safe Food from Production to Consumption.”

In this report, the committee made a number of suggestions that included the following:

- Congress should consider enacting comprehensive, uniform, and risk-based food safety legislation.

- There should be established a single, independent food safety agency at the Cabinet level.

- If Congress did not opt for an entire reorganization of the food safety system, it should consider modifying existing laws to designate one current agency as lead agency for all food safety inspection matters.

- Congress and the administration should require development of a comprehensive national food safety plan.

- Funds appropriated for food safety programs (including research and education programs) should be allocated in accordance with science-based assessments of risk and potential benefit.

The idea of a national food safety plan was beneficial for the integration initiative, as it recommended the plan include a unified, science-based food safety mission and integration of federal, state, and local food safety activities.

The report specifically addressed the federal role in the food safety system, but indicated the roles of state and local government entities were equally critical. It further stated the work of the states and localities in support of the federal food safety mission deserved better formal recognition and appropriate financial support.

Now, the matter of a single, independent food safety agency continues to be debated to this day. Many state and local officials have stayed somewhat silent on the matter; they believe state and local agencies would continue to perform the majority of food safety work whether there was one federal agency or multiple agencies. We remain confident that government integration is still be needed.

NATIONAL FOOD SAFETY SYSTEM PHASE TWO: PLANNING THE VISION. The first NFSS Coordinating Committee meeting was held March 1-3, 1999, in St. Louis, Mo. Here, a NFSS Mission Statement was agreed upon: “Our mission is to develop and promote a national Integrated Food Safety System (IFSS) to best serve the public’s health.”

The committee agreed that a fully integrated food safety system must consist of common ownership by federal, state, and local government agencies organized to reduce or eliminate foodborne illness and injury and ensure that foods are safe, wholesome, and honestly represented. This would be accomplished by developing, promoting, and implementing food safety strategies to clarify the roles and responsibilities of all levels of government, enhance data sharing and collection, facilitate system-wide communication, establish minimum uniform standards, improve laboratory operations and coordination, and improve outbreak responses and investigations. This was quite a tall order, but federal, state, and local officials looked forward to the challenge.

Work began at this meeting by identifying what we believed were properties of an integrated system:

- Strong national standards

- Competence of inspection, investigation, and surveillance

- Adequate training and certification

- Effective information, communication, and data sharing

- Federal oversight

- Credible enforcement programs

- National uniformity

- Responsiveness

- Knowledgeable public

Now, the matter of a single, independent food safety agency continues to be debated to this day. Many state and local officials have stayed somewhat silent on the matter; they believe state and local agencies would continue to perform the majority of food safety work whether there was one federal agency or multiple agencies. We remain confident that government integration is still be needed.

After the first 50-state meeting the previous year, work groups began developing ideas, and work group chairs presented these to the Coordinating Committee. The ideas were huge in innovation and provided an exciting avenue to accomplish the goals and objectives of NFSS. Here are a few of the innovative ideas presented to the Coordinating Committee:

- Create an oversight and audit program to assure inspection consistency.

- Establish a national food safety training center.

- Design a model integrated food safety system partnership agreement to deploy between FDA districts and states.

- Develop guidelines for coordinating multistate foodborne illness outbreaks and tracebacks.

- Create an integrated regulatory and public health data system maintained through a dedicated staff. Data categories include information relative to surveillance, consumer complaints, source identification, outbreaks, and enforcement.

- Establish a USDA/FDA/EPA/CDC toll-free hotline as a single point of contact for state and local agencies.

- Establish an early warning system when potential outbreak information occurs in different locations.

- Develop program standards initially applied to retail foods, manufactured foods, seafood, meat & poultry, milk & milk products, and produce.

- Identify the responsibilities and capacity of federal, state, and local laboratories performing food safety testing.

- Develop national standards for equivalency of food sampling, testing methods, and lab data exchange.

- Establish a lab accreditation system that examines and evaluates the capacity of a laboratory to generate high-quality, reliable test results.

It is noteworthy that many of these innovative ideas presented in 1999 to the Coordinating Committee were accomplished even after the termination of the NFSS project that soon followed.

THE END OF NFSS, 2002. A lot of work led to a lot of anger as the NFSS project began to lose its funding in 2002, and the vision for an integrated food safety system appeared doomed. NFSS work groups were disbanded and the 50-state meetings were discontinued. Some of the innovative ideas continued to be pushed by FDA, but the energy and enthusiasm that had once existed was gone. This continued for several years.

Things seemed to really fall apart in 2005, when Lester Crawford was appointed FDA Commissioner — he was not regarded as a strong supporter of state and local food safety programs. There were new leaders in FDA as well who believed state and local programs were terribly inept and should only be allowed to conduct FDA inspections at low-risk types of establishments such as food warehouses. These new FDA leaders did not have a good concept of how state and local agencies operated: Our philosophies for inspection, compliance, and enforcement were so different. FDA inspections were focused on obtaining evidence for enforcement actions, while state and local agencies focused on obtaining compliance. States and locals even provided educational programs for establishment operators, which was foreign to what FDA would do. In addition, state and local agencies issued licenses or permits to allow food establishments to operate; when these firms were unable to gain compliance, the license or permit would be revoked.

Soon, however, Crawford resigned, and Andrew C. von Eschenbach (Fig. 10) became the Acting FDA Commissioner and then FDA Commissioner. FDA was promoting its Food Protection Plan at the time, which called for better coordination with state and local officials. Commissioner von Eschenbach soon voiced the agency’s support for advancing an integrated food safety system, but this was met with great skepticism from state and local officials. I remember one local health official asking him very pointedly during another 50-state meeting, “Why should we believe you?”

The objectives of FDA’s Food Protection Plan seemed to parallel the goals of the NFSS project. These goals were to establish a system that would better utilize and leverage all the committed food safety resources (at all levels of government), build uniformity and consistency (with inspectional, analytical, enforcement, and surveillance activities), increase the level of consumer confidence by improving food safety, and implement ONE food safety system. It appeared we were back to developing an integrated food safety system.

NATIONAL FOOD & AGRICULTURE LAB COMMITTEE, 2004. There was one project survivor when NFSS project funding was eliminated — the formation of the National Food & Agriculture Lab Committee (NFALC). NFALC was an idea of the NFSS Lab Capacity and Coordination Work Group. NFALC was created at the 108th AFDO Annual Conference in 2004. There, an interim ad hoc work group was set up to help define the mission, vision, and goals for this effort and to introduce protocols to govern the NFALC. The ad hoc work group’s members were selected from laboratory directors who were actively involved in advocacy on a national basis for the interests of agriculture control official laboratories. The USDA provided initial funding to host the charter meeting where the ad hoc work group developed mechanisms to select appropriate candidates to serve on a steering group for the new committee.

This larger steering group helped guide the formation and mobilization of the NFALC on a 50-state basis. The vision of NFALC was to be the national committee on technical, scientific, and policy issues representing state agriculture control laboratories to associations, agencies, and regulators of agriculture and food products. NFALC would provide a voice and leadership for state agriculture control laboratories throughout the country.

2004 GAO REPORT. In 2004, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report entitled “Fundamental Restructuring Is Needed to Address Fragmentation and Overlap.” GAO concluded that, given the risks posed by new threats to the food supply, the nation could no longer afford inefficient, inconsistent, and overlapping programs and operations in the food safety system. GAO believed that creating a single food safety agency to administer a uniform, risk-based inspection system was the most effective way for the federal government to resolve long-standing problems, address emerging food safety issues, and better ensure the safety of the nation’s food supply. The office did indicate that integration through a single food safety agency would create the synergy necessary to provide more focused and efficient efforts to protect the nation’s food supply.

SINGLE FOOD SAFETY AGENCY. The Safe Food Act of 2005 S. 729 introduced by Senator Richard Durbin (D-IL) on April 6, 2005, and its companion bill, H.R. 1507, introduced by U.S. Representative Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), called for an integrated system-wide approach to food safety. The bills criticized outdated laws and the fragmented federal food safety system, which were serious impediments to efficient deployment of food safety resources and the effective prevention of foodborne illness.

Under the newly proposed regulatory scheme, all food safety labeling, inspection, and enforcement activities would be transferred to a new agency to be called the “Food Safety Administration.” This would include the activities of the USDA Food Safety & Inspection Service, USDA Agricultural Marketing Service (shell egg surveillance), USDA Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service, FDA Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition, FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine, FDA Office of Regulatory Affairs, Environmental Protection Agency (pesticide residue in foods program), and National Marine Fisheries Service (seafood inspection program).

AFDO sent representatives to personally meet with Congresswoman DeLauro (Fig. 11) to discuss the proposed rule and inform her of the critical role of state and local programs regarding food safety and public health.

Congress continued to push for a single food safety agency in the coming years. In 2010, the Single Food Safety Agency Act of 2010 was proposed. It would again establish the Food Safety Administration as before and would include agencies involved with improving research on contaminants leading to foodborne illness and improving security of food from intentional contamination.

In 2018, the Trump Administration proposed to consolidate FSIS and FDA’s food safety functions into a single “Federal Food Safety Agency” to be housed at USDA. According to the administration, this effort would address a “fragmented and illogical division of federal oversight” and “merge approximately 5,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees and $1.3 billion from FDA with about 9,200 FTEs and $1 billion in resources in USDA.” FDA would be renamed the “Federal Drug Administration” with a focus on drugs, devices, biologics, tobacco, dietary supplements, and cosmetics.

The objectives of FDA’s Food Protection Plan seemed to parallel the goals of the NFSS project. These goals were to establish a system that would better utilize and leverage all the committed food safety resources (at all levels of government), build uniformity and consistency (with inspectional, analytical, enforcement, and surveillance activities), increase the level of consumer confidence by improving food safety, and implement ONE food safety system.

In 2022, Congresswoman DeLauro and Senator Durbin introduced legislation to remove food safety oversight functions from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Called the “Food Safety Administration Act,” it would establish the Food Safety Administration under the Department of Health and Human Services. The single food safety agency would remove existing food programs within FDA, and leadership appointments would require Senate confirmation.

The legislation does not include the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) of the USDA.

The single food safety agency proposed by DeLauro and Durbin would remove existing food programs within the FDA, and leadership appointments would require Senate confirmation. The Food Safety Administration would consist of the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN), Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM), and the Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA). The agency would be headed by the Administrator of Food Safety and appointed by the president.

The FDA would be renamed the Federal Drug Administration and would retain oversight of drugs, cosmetics, devices, biological products, color additives, and tobacco.

AFDO RESPONDS TO NEW FEDERAL FOOD SAFETY LEGISLATION, 2008. As new food safety legislation was being proposed, AFDO issued a position statement in response. In the statement, AFDO voiced its support for a fully integrated food safety system, but did not offer a position on a single food safety agency. AFDO stated that any federal food safety legislation that failed to recognize the efforts and impact of state and local food safety regulatory agencies was destined to fail, as the overwhelming majority of food safety efforts are conducted at the local and state levels. AFDO further stated that food safety was not a federal responsibility alone but a shared responsibility of government at all levels, industry, and consumers. AFDO also indicated that any federal food safety legislation must be consistent with the following points:

- Make it easier to share public health information.

- Expand and fund cooperative programs.

- Expand state and federal recall authorities.

- Accept state inspection and analytical data.

- Align responsibilities with agreed upon roles.

- Leverage states for inspecting imported food.

- Creation of a budget line item for state funding.

- Double the value of new federal funding by funding state regulatory programs.

- Expand mandatory HACCP to all food processing.

STRONGER PARTNERSHIPS FOR SAFER FOOD — AN AGENDA FOR STRENGTHENING STATE AND LOCAL ROLES IN THE NATION’S FOOD SAFETY SYSTEM, 2009. Michael Taylor (Fig. 12) and Stephanie David from George Washington University were leaders in the development of a report entitled “Stronger Partnerships for Safer Food — an Agenda for Strengthening State and Local Roles in the Nation’s Food Safety System.” This gave a huge boost to the integration effort, as the report illustrated the critical importance of state and local agency food safety efforts.

The Association of Food and Drug Officials (AFDO), Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO), and the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) assisted in the project, which was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The report illustrated how national policymakers focused their food safety reform efforts on the key federal food safety agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Department of Agriculture (USDA). However, the report clearly showed that these federal agencies were just the tip of a much larger pyramid of state and local agencies working on food safety. It concluded that state and local health and agriculture departments were the foundation of the nation’s food safety system, with primary responsibility for illness surveillance, response to outbreaks, and regulation of food safety in more than millions of food establishments. State and local agencies collectively conduct many more inspections, test many more food samples for harmful contamination, and bring many more food safety enforcement actions than the federal food safety agencies. The report stated specifically: “Food safety reform will not be complete or successful unless the efforts of these agencies are strengthened and integrated more fully into the national food safety system.”

Michael Taylor was an ardent supporter of state and local programs and became a true champion of the effort to integrate the food safety system. He soon became FDA Deputy Commissioner in the Office of Foods under FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg, where he assisted in the planning and implementation of new food safety legislation and the advancement of IFSS projects and initiatives.

PARTNERSHIP FOR FOOD PROTECTION, 2009. A significant high point for advancing an IFSS was the formation of the Partnership for Food Protection (PFP) (Fig. 13). This followed a number of large-scale food outbreaks, which heightened public awareness of food safety. PFP became the driving force behind IFSS just as the NFSS project was in earlier years. PFP comprises an Executive Committee, Coordinating Committee, and six work groups.

The work groups and their primary functions are as follows:

- Information Technology — Promote data standards to improve the ability to share information electronically among strategic partners.

- Laboratory Science — Create resources that build confidence among stakeholders in the integrity and scientific validity of laboratory analytical data and facilitate acceptance of laboratory analytical data by regulatory agencies.

- Outreach — Communicate the importance and benefits of an integrated food safety system and mutual reliance.

- Surveillance, Response, and Post-Response — Promote increased collaboration, share lessons learned, and identify needed improvements with surveillance and response activities.

- Training and Credentialing — Help develop standard curricula and certification programs to promote consistency and competency among the IFSS workforce.

- Work Planning, Inspections and Compliance — Coordinate approaches in planning and conducting industry oversight activities.

PFP comprises representatives with expertise in food, feed, epidemiology, laboratory, animal health, environment, and public health leading the development and implementation of integration. It is not, however, a policy setting organization. Its primary function is to promote communication and integration between all jurisdictions and provide resources, risk-informed insight, and best practices to improve the system partners can utilize to inform and enhance their work in protecting public health. PFP’s vision is “Mutual reliance for a safer food supply.”

PFP has reignited the energy and enthusiasm for building the integrated food safety system.

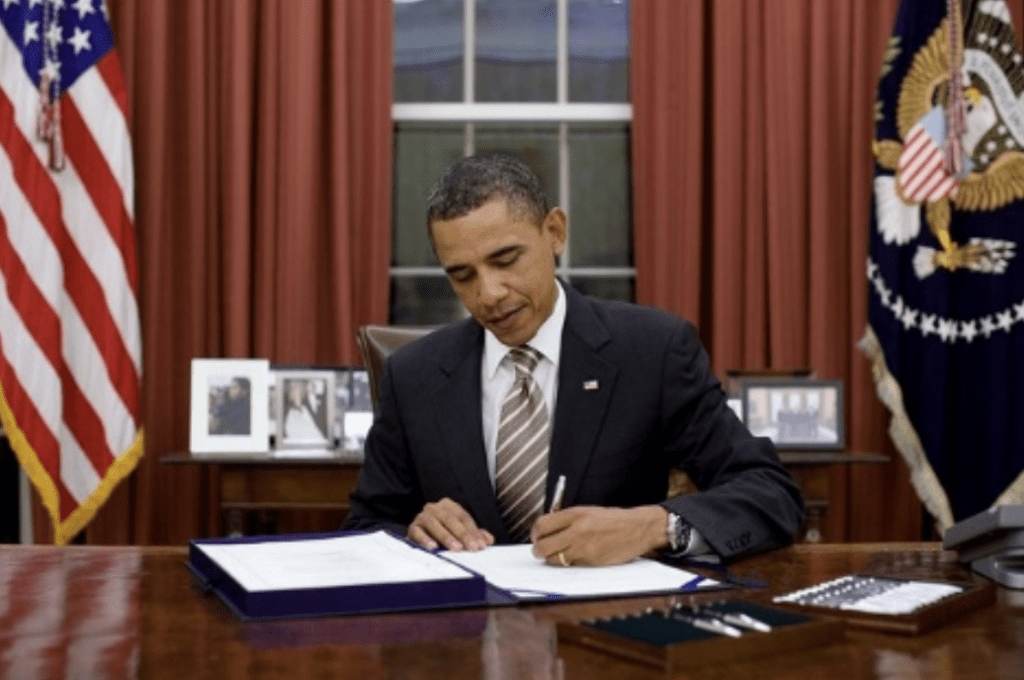

FOOD SAFETY MODERNIZATION ACT, 2011. President Barack Obama signed the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) into law on Jan. 4, 2011 (Fig. 14). The law was the most comprehensive reform of our federal food safety laws in over 70 years. It provided FDA new authority to regulate the way foods are grown, harvested, and processed, and it granted FDA a number of new powers, including mandatory recall authority.

FSMA required FDA to undertake more than a dozen rulemakings and issue at least 10 guidance documents, as well as a host of reports, plans, strategies, standards, notices, and other tasks.

FSMA was designed to build a formal system of collaboration with other government agencies, both domestic and foreign. In doing so, the statute explicitly recognizes that all food safety agencies need to work together in an integrated way to achieve our public health goals. Specifically, FSMA requires FDA to develop and implement strategies to leverage and enhance the food safety and defense capacities of state and local agencies. It also provides FDA with a new multiyear grant mechanism to facilitate investment in state capacity to more efficiently achieve national food safety goals.

“Food safety reform will not be complete or successful unless the efforts of these agencies are strengthened and integrated more fully into the national food safety system.” — Stronger Partnerships for Safer Food — an Agenda for Strengthening State and Local Roles in the Nation’s Food Safety System

FSMA was the statute that finally validated FDA’s desire to build an integrated food safety system. This was confirmed by former FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg (Fig. 15) in her remarks to the U.S. House Appropriations Subcommittee: “FDA’s successful implementation of FSMA is essential to reducing foodborne illness, bolstering public confidence in the food supply, and maintaining U.S. leadership on food safety internationally. With FDA under court order to issue many key FSMA regulations in 2015, FY 2016 is an absolutely crucial year for the investments needed to ensure timely, effective, and non-disruptive implementation. FDA’s collaborative implementation strategy requires a modernized approach to inspection and enforcement, focusing on food safety outcomes and encouraging voluntary compliance. To be successful, this strategy requires retraining and retooling of FDA and state inspectors. In keeping with FSMA’s theme of collaboration and partnerships, the largest single portion of the budget authority will go to the states to better integrate, coordinate, and leverage federal and state food safety efforts.”

Unlike the initiatives FDA had promoted in previous years, FSMA was a law that mandated FDA to better coordinate with its inspection partners. This was such a huge shot in the arm for the integration effort.

MUTUAL RELIANCE. The establishment of Mutual Reliance programs became our way forward to building the national integrated food safety system. They will be the seamless partnerships that enable FDA and state and local agencies to rely on, coordinate with, and leverage one another’s work, data, and actions. These partnerships are made possible through state and local compliance with regulatory program standards, which validates comparable regulatory public health systems. They allow agencies to become trusted partners and open many opportunities for sharing information and working in a more coordinated fashion.

Already, we see collaboration growing in many areas including:

- Data exchange/information sharing

- Work planning and risk prioritization/categorization, including inspection frequency mandates, and comparison and reconciliation of inventories

- Acceptance of other agency inspection, compliance/enforcement, and corrective actions

- Food testing to support FDA actions

- Environmental assessment

- Recall oversight and effectiveness/audit checks

- Investigation of outbreaks and complaints

- Sample collection and laboratory capacity, analysis, and reporting

- Field staff training

- Industry and consumer education

- Organizational resources and personnel

- Development and monitoring of key mutual reliance metrics

Mutual reliance efforts should establish the collaborative infrastructure of an integrated food safety system and improve the quality and integrity of our public health and food protection work. They should also improve industry and consumer confidence in regulatory programs and in the nation’s food supply. They will create the integrated food safety system we have envisioned and will confirm for all federal, state, and local food protection officials, from the field inspector to the program manager, that they are all part of ONE food safety system.

NEVER GIVE UP, AND NEVER GIVE IN. The 25 years we’ve invested is only a long time if you think it wasn’t a good time for improving our food safety system. One need only refer to the FDA’s webpage, “National Integrated Food Safety System (IFSS) Programs and Initiatives” under “IFSS Major Initiatives, Programs, and Projects” to understand and realize all the work that’s been achieved. The milestones can also be viewed in a timeline found here.

This is a truly remarkable effort in striving to achieve something so many felt could not be accomplished — something that required the impossible task of changing governmental agency cultures.

What I find myself being most proud of is how the food protection and public health community never gave up or gave in to the barriers, obstacles, and cynics that were confronted. It was not always easy and clearly filled with frustration along the way. We dealt with the loss of funding, numerous FDA reorganizations, and a few federal leaders who did not trust or even like state and local agencies. We pressed on when our efforts were rejected and built alliances, partnerships, and networks. We turned every setback into a comeback, and this only made our mission stronger.

Consumer groups who were once very opposed to integration are now supportive, and today, FDA is looking at even more opportunities for improving collaboration with industry.

So much has been completed, but there is more to do — and we will do it with new leaders and a whole new generation of food protection officials. It may take another 25 years, but it will be worth it.

References:

Journal of the Association of Food and Drug Officials: Volume 61; No.4; December 1997; “Regulatory Cooperation over the Next Five Years”; Panel Presentation by Dan S. Smyly, Ph.D.; Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society (RAPS) Conference, September 9, 1997 in Washington, D.C.

United States Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service, Third Annual Federal/State Conference on Food Safety; “Partnerships to Improve Food Safety”; Sacramento, CA; November 20-21, 1997

Integrated National Food Safety System; “Meeting Challenges Together”; Phase 1 Creating the Vision; Executive Summary of the National Food Safety System (NFSS) Coordinating Committee; Kansas City, MO.; September 1-17, 1998

Integrated National Food Safety System; “Meeting Challenges Together”; Phase 2 Planning the Vision; Executive Summary of the National Food Safety System (NFSS) Coordinating Committee; Baltimore, MD.; December 8-11, 1998

National Academy of Science; “Ensuring Safe Food from Production to Consumption; 1998; https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/6163/ensuring-safe-food-from-production-to-consumption

AFDO Journal; Volume 62, No.3, September 1998; “Food Safety VINE (Vertically Integrated National Enterprise) “An AFDO Vision”; Joseph Corby

Journal of the Association of Food & Drug Officials: Volume 8; No.4; December 2004 AFDO Journal; “The National Food and Agriculture Laboratory Committee (NFALC)”; William R. Krueger; https://www.afdo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Volume-68-%E2%80%93-No.-4.pdf

Federal Food safety and Security System; “Fundamental Restructuring Is Needed to Address Fragmentation and Overlap”; March 30, 2004: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-04-588t.pdf

Partnership for Food Protection (PFP); https://www.pfp-ifss.org/

Partnership for Food Protection (PFP) Workgroups; https://www.pfp-ifss.org/workgroups/

“Stronger Partnerships for Safer Food: An Agenda for Strengthening State and Local Roles in the Nation’s Food Safety System”; Michael Taylor and Stephanie David; George Washington University; 2009; https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_policy_facpubs/527/

Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA); https://www.fda.gov/food/guidance-regulation-food-and-dietary-supplements/food-safety-modernization-act-fsma

National Integrated Food Safety System (IFSS) Programs and Initiatives; https://www.fda.gov/federal-state-local-tribal-and-territorial-officials/national-integrated-food-safety-system-ifss-programs-and-initiatives

Domestic Mutual Reliance; https://www.fda.gov/federal-state-local-tribal-and-territorial-officials/national-integrated-food-safety-system-ifss-programs-and-initiatives/domestic-mutual-reliance

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- IFT DC Section to Host Food Policy Event Featuring FDA, USDA Leaders

- CSQ Invites Public Comments on Improved Cannabis Safety, Quality Standards

- Registration Open for IAFNS’ Fifth Annual Summer Science Symposium

- Leaked White House Budget Draft Proposes Shifting Inspection Responsibilities from FDA to States

- Chlorine Dioxide: Reset the Pathogenic Environment

- Ferrero Group Invests $445 Million in Ontario Production Facility

- Nelson-Jameson Announces Grand Opening for Pennsylvania Distribution Center

- Taylor Farms Linked to Romaine E. coli Outbreak as Marler Clark Files Multiple Lawsuits Against Supplier