You Zhou (UNL) and Rong Wang (ARS)

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Disease-causing bacteria like E. coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica could survive sanitization in beef processing facilities. Scientists and collaborators in the Department of Agriculture’s (USDA), Agricultural Research Center (ARS) are investigating how this happens while also seeking approaches to solve the problem.

E. coli O157:H7 (a Shiga toxin-producing E. coli) and S. enterica are two disease-causing bacteria (pathogens) associated with foodborne illnesses in the United States. Because these pathogens can make people sick through contaminated food, scientists are researching effective and economical ways to lower risks of cross-contamination at food processing facilities.

In a study, scientists explained the survival behavior of E. coli O157:H7 after exposure to unfavorable conditions such as those created by routine sanitation procedures, and how it varies within beef processing facilities that are following similar sanitizing protocols.

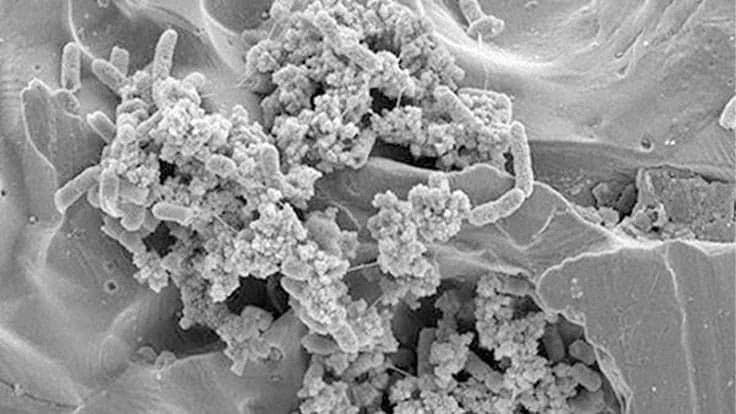

"Under certain conditions, pathogens like E. coli O157:H7 and S. enterica would enter into a dormant or 'hibernation' stage, forming a thin film that allows it to better survive on hard surfaces such as concrete or steel. This is called a bacterial biofilm, and it cannot be seen with the naked eye," explained Dr. Rong Wang, research microbiologist with U.S. Meat Animal Research Center in Clay Center, Neb.

A major concern is that biofilms allow harmful bacteria to better survive on hard surfaces at the facility, potentially contaminating food, and making consumers sick. Interestingly, studies show that these pathogens do not survive on their own. After comparing samples from different facilities that follow similar cleaning measures but experiencing different levels of pathogens, scientists learned that multiple species of bacteria found in the processing plant environment of each location could either enhance or reduce a pathogen’s chance of surviving sanitizing procedures. They do this by forming a biofilm community (mixed biofilm structure).

"We look at the unique communities of environmental bacteria that collaborate or compete with pathogens at each location," said Wang. "The collaboration may lead to high pathogen prevalence at certain locations, but strong competition may inhibit pathogen survival at other places. Since many of these environmental bacteria are not harmful to humans or animals, if we can identify the specific species that inhibit pathogen biofilm formation, we can use them as probiotics (preventive measures) against disease-causing bacteria."

Meanwhile, a couple of studies published in the Journal of Food Protection from this research group show that multi-component sanitizers, a novel multifaceted approach using combinations of various sanitizing reagents and treatments could inactivate biofilms formed by E. coli O157:H7 and S. enterica more effectively, reducing the chances of the pathogen surviving cleaning practices at beef processing facilities.

More research is needed to understand the interaction of multiple species of bacteria present in different processing plant environments and how they vary from one facility to another — reflecting different locations, temperatures and other factors.

Latest from Quality Assurance & Food Safety

- Kim Heiman Elected to Second Term as President of Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association

- FAO Launches $150 Million Plan to Restore Ukrainian Agricultural Production

- Pet Food Company Implements Weavix Radio System for Manufacturing Communication

- Penn State Offers Short Course on Food Safety and Sanitation for Manufacturers

- USDA Announces New Presidential Appointments

- FDA to Phase Out Petroleum-Based Synthetic Dyes in Food

- IFT DC Section to Host Food Policy Event Featuring FDA, USDA Leaders

- CSQ Invites Public Comments on Improved Cannabis Safety, Quality Standards